#113: The new quantified self

Read 200 books, expand your consciousness 200x!

This morning I went on a stroll around my neighborhood and, according to my phone, took 3,503 steps. On the walk, I passed a bunch of toddlers holding hands, looked into an abandoned storefront and imagined it on its opening day, and saw a man walk silently down the street with his head in a cloth bag, two holes cut out for his eyes. More than likely, I will forget all that (okay, maybe not the literal horror movie villain?), but my phone will remember the steps, and I will later use that data to determine how “active” I was in 2022. Despite how little my step count will tell me about my life, I’ll accept it as a meaningful measure anyway.

A lot has been said about the quantified self—that it will save us, that it makes us anxious, that it’s dead, or maybe alive again?—and usually the conversation centers around the tracking of things like step counts, heart rates, sleep patterns, and dietary habits. But I’d argue any objective measure of self could be included: how many movies we watch, books we read, followers we have, how much money we make—basically anything about our lives that we can count. As tracking tools become increasingly sophisticated, and more importantly, built into how we operate (like my phone counting my steps just by being in my pocket), the profundity of their findings is basically assumed. At the end of the year, for example, when Pocket tells me how many articles I’ve read and Spotify tells me who I listened to the most, I pore over the information like a diagnosis, then forget about it shortly after.

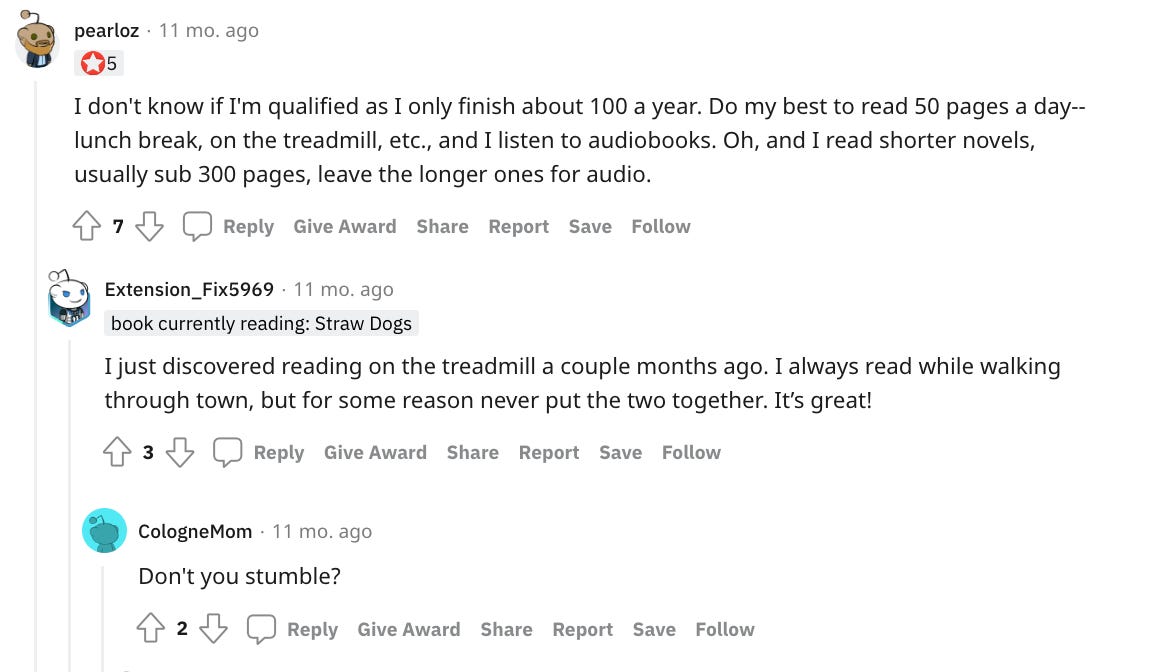

I started thinking about this when my For You page on Tiktok surmised I might be interested in the super-reader community, and showed me a few posts of people talking about how many books they’d read this year. The people I saw were tracking and logging books in apps like Goodreads or in custom, multi-colored spreadsheets. I consider myself a pretty active reader, but their numbers terrified me: 200 or 300+ books a year. What does it functionally look like to read that much? In a Reddit thread that poses the same question, you can find practical hacks for consuming art quickly, such as, “setting a page/chapter target, for example, 50 pages per day (assuming you read a page per minute) that’s less than an hour. Then once you’re comfortable with that and finding it too easy/fast extend it by 10 until you achieve your desired goal!” If you’d like to know more about fine art, feel free to swap out “pages” for “paintings.”

Here are some more tips:

Obviously the more pressing question than how to read this much is why. Stumbling through the street to finish a chapter feels like the perfect metaphor for losing the plot. In this Inc.com piece from 2017 called “Read 200 Books This Year by Making This 1 Tiny Change to Your Routine” (it’s quitting social media, lol), the author presumes the point of reading so much is to get smart: “There’s no secret to how to get smarter. You read. A lot. Really, that’s it. And if you don’t believe me, there’s a whole host of luminaries, from Warren Buffett and Bill Gates to Richard Branson and Barack Obama, who will tell you the same thing.” Ah yes, rich and power-hungry men, famously the smartest people on Earth.

I’ve so far finished 19 books this year, which I will admit to tracking privately in an iPhone note. I will even admit to comparing my 2022 numbers to previous years. But not until I passed through the maniacal, super-reader side of BookTok did I consider the value judgment baked into that endeavor: that more books is necessarily better. Generously, I associate more reading with less TV and/or mindless scrolling, which feels good. But just because books have the power to expand my consciousness doesn’t mean every book does, or that I’m reading them in the best way to do that. Sometimes my pace feels so fast—my need to start a new book almost neurotic—that I fail to let their messages sink in. Binge-reading may feel less brain-melting than binge-watching, but they share a lot of qualities: the obsession, the escapism, the desperation to know what happens next. It’s books in the realm of entertainment, versus the realm of art.

Which is fine, of course; anyone can read for whatever reason they want. Most activities that aren’t staring into our phones, brains turned to white noise, seem healthy in comparison. Ironically, however, treating reading like a competitive sport—tracking, logging, maximizing our productivity and comparing it against our peers—seems like an impulse inspired by technology itself. We’re data mapping our art consumption. Who says speed-reading 200 YA novels is better than reading one book slowly and thoughtfully, and then reading it again? “We have this mentality that metrics are more accurate or more insightful than other ways of learning about ourselves,” professor Deborah Lupton told Rachael Sigee in a recent Guardian piece about why we love to track these things. At the end of the article, Sigee makes plans to downgrade her tracking habit to a “companion” in her life rather than a driving force, but I wonder how much of that is in her control.

Quantitative measures are more appealing to us than qualitative ones because they’re empirical and observable, and crucially, because we can pit datapoints against each other. As social creatures who constantly compete and also fear the uncertain and unknown, this affinity isn’t surprising. But technology, being limited in its ability to translate the world’s softer, squishier parts, has simply just led us deeper into the project of objectifying everything. Friends that can be counted, tastes that can be checked like boxes, personalities that can be summed up with labels, fitness that can be tracked and analyzed. It’s a lot easier and more immediately satisfying to rely on concrete data than something borderless like intuition or feeling. It’s also a crutch—a perfect balm for insecurity that can secure us in only one specific way, and not always in the way we think.

When mindfulness and meditation became popular in Silicon Valley, for example—clearly in response to our increasingly distracted lives—our reaction was to adapt the practice to a digital routine. Mediations minutes logged, goals met, reward widgets granted. “A less arrogant industry might have settled for warning labels on its phones and pads, but Silicon Valley wanted an instant cure, preferably one that was hi-tech and marketable,” the late Barbara Ehrenreich wrote in a piece about meditation apps for The Baffler in 2015. (I recommend reading it in full—the kicker is bone-chilling.) Meditation, notoriously difficult, made easy? The ads write themselves. (Popular meditation app Headspace made $150M in 2020. Take that, Buddhism.)

I started paying more attention to my daily step count when I realized how much my averages had fallen off in 2020 and 2021. This alarmed me, as if I hadn’t personally been present for the pandemic that radically altered my reality. Now I check it almost every day and attempt to lift my numbers. I tell myself this is the same as caring about my health, but it feels more like playing a video game. When I’m unusually active—15,000 or 20,000 steps on a Saturday, say—checking my Health app in the evening feels like collecting my winnings. Whether or not I’ve actually practiced healthy habits that day, I’ve won. It’s a cheap thrill that comes at a subtle cost, which is that I’ve come to believe my phone can tell me whether I’ve moved enough better than my body can.

In a TechCrunch piece last month about how entrepreneurs are solving for mortality, that pesky thing, venture capitalist Samuel Gil weighed in on the promise of the quantified-self movement. “I find it very gross that we know in real time what is happening in our cars,” he said, “but we have no clue what’s going on inside our bodies.” But is that true? Do we actually have no idea what’s going on in our minds and bodies, or have we just lost touch with those innate tools? “Continuous monitoring is going to be a reality at some point,” Gil concluded. I’m sure he’s right; maybe it will make him very rich.

Despite my persistent techno-pessimism, I’m not functionally a luddite. In fact, my attraction to technology feels foundational and thus frightening. I grew up in Silicon Valley—Mountain View, specifically. New tech still codes in my brain as electrifying. When I recently had my feet 3D-scanned at a shoe store, the results were like a drug to me (“omg this kind of self knowledge is a DREAM,” my friend Charlie DM’d when I posted photos, and I agreed). But after the novelty wore off, there was less to do with the information than I hoped. It had confirmed my feet were asymmetrical, but I already knew that.

It’s easy and probably correct to blame this cresting alienation from ourselves on Silicon Valley vultures with their dopamine fasts, reverence for control, and profit motives to collect and sell our data. Through them, we’ve accepted productivity as our god. But it’s also useful to think about the broader ideology we’ve subscribed to as a society about what it means to know ourselves and to live well. There is something fundamentally fearful about our desire to quantify our lives—art consumed, habits codified—as if we can stave off death by measuring its antecedent in infinitely smaller units. It takes a certain trust to move forward without proof, but unfortunately we outsourced that a long time ago, and it’s hard to imagine turning back now.

My favorite thing I consumed last week was KATE, Kate Berlant’s new solo comedy show at Connelly Theater. Friday’s 15 things also included yet another beloved kitchen purchase, the perfect fall album, an actually useful iPhone hack, and more. The Rec of the Week was mattress tips/tricks/general wisdom. (I’m in need of a new mattress and am determined to find the perfect one).

Hope you have a nice Sunday!

Haley