Last Sunday was the New York City marathon, arguably one of the best days to live here. I dragged Avi to Bedford and Lafayette after breakfast to watch the elite pack-leaders go by (nearly sprinting) and sent videos to my family, the sound of screaming spectators already drowning out the first footsteps of the day. “The annual marathon cry,” my sister replied, and I agreed. The day before, Harling told me a TikTok that merely outlined the route had her in tears. She’d been looking it up so we could catch our friend Amelia running by, which we did around 1pm on Sunday, at the 10-mile mark, as we jumped and yelled then laughed as we watched each other’s eyes pool. “Amazing but doesn’t give me the urge to cry at all,” my mom eventually texted back. “Probably because I've never been a runner.” I told her that wasn’t it—she’d get it if she were there. She’d be crying, I was sure. Everyone was!

The New York City marathon is a total spectacle: 50,000 people run it and over a million come out to cheer them on. You’re likely to see every type of person imaginable jogging by (an old man in a beanie, a young woman eight months pregnant, everyone pushing their specific limits) and any number of random things being passed out to them by spectators (bananas, ziploc baggies of ice, paper cups of gummy bears, hoarse cries of encouragement, glitter). The route starts in Staten Island and snakes through Queens and Brooklyn, finishing in Manhattan. It seems unbearably long. Harling and I kept having to remind ourselves that Amelia, hours after we’d first seen her, was still running. We marveled every time.

Marathons are prime producers of art tears. There’s something so moving about the runners’ bare display of humanity—their willingness to suffer together in search of meaning—and the spectators’ naked, unspecific support. All of it seems to suggest humans aren’t actually geared toward ease, comfort, and caring about ourselves; that defining us that way is, at the very least, incomprehensive. The whole thing is life-affirming in a way few modern spectacles are. I’ve written about all this before, but it’s been three years and I have new things to say, by way of a much wilder, weirder race.

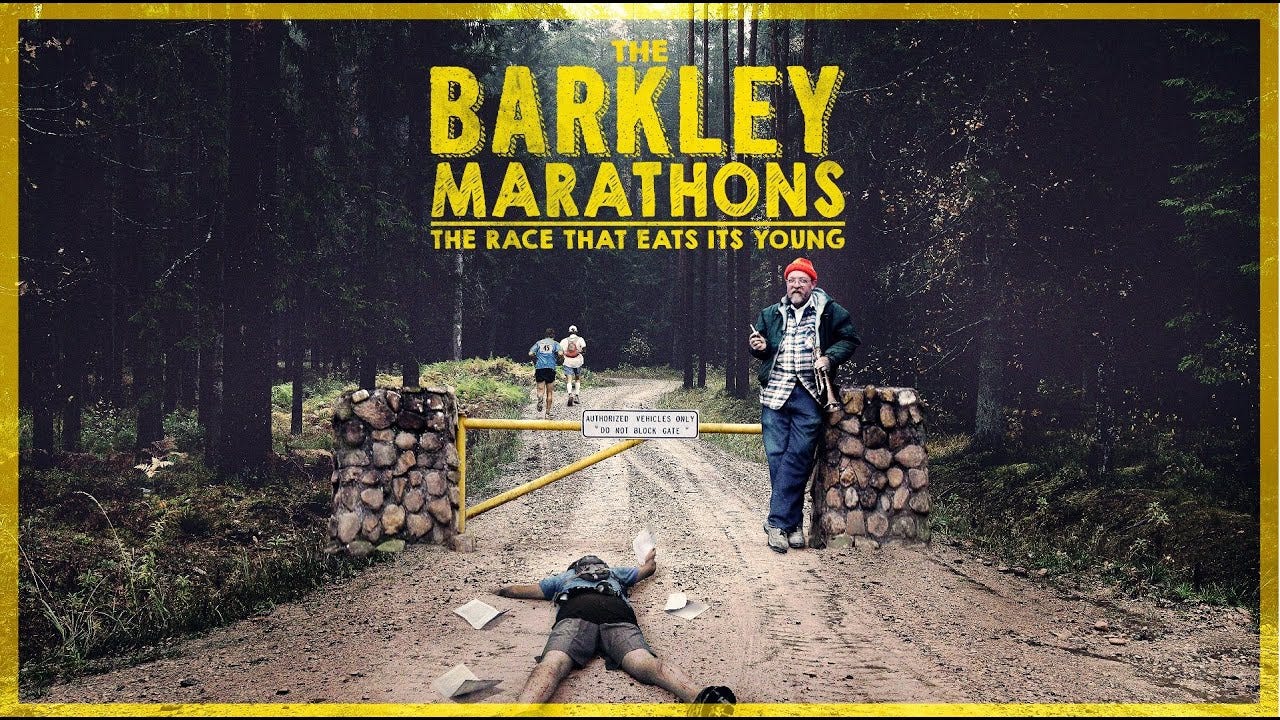

Around 91st Street, while we waited to watch Amelia run by at mile 23, Harling insisted I watch the documentary about the Barkley Marathons. We’d just seen a runner collapse as if blacked-out drunk on the race path. Cops crowded around while a woman kneeled to feed him sips of Gatorade. He feebly accepted. Our hearts sank imagining his disappointment at not finishing, so close. It seemed like an entirely understandable way to feel (disappointed) but also cruel and wrong, considering how hard he’d tried. Later, when I got home, I Googled the documentary. The Barkley Marathons, it was called, The Race That Eats Its Young. I watched it the next day, and then again a few days later. It’s been stuck in my head all week, lending new depths to my fascination with marathons.

The Barkley

Created “out of thin air” by a strange guy known as “Laz,” often smiling threateningly behind a bushy backwoods beard, and his friend “Raw Dog” (lol), some don’t even consider the Barkley Marathons a real race. There are many reasons for that: the exact mileage is unknown; the trail is unmarked and GPS is prohibited, meaning runners are all but guaranteed to get lost; it starts any time Laz decides to blow a conch shell between midnight and 12pm, at which point runners have one hour to prepare before gathering at the starting line to wait for Laz to light a cigarette, which signals the official start of the race. The application costs $1.60 and the 40 accepted entrants are required to come bearing either a license plate from their home or a random household item Laz needs, like a new pair of socks or a flannel. Some consider it the toughest trail race in the world, and it enjoys a cult-like status among ultramarathon athletes.

Here’s how the Barkley works: Runners must complete five 20-ish-mile loops (closer to 26 miles, many believe) in less than 60 hours. That’s five consecutive marathons through the wild Tennessee mountains in 2.5 days with little to no sleep. The route is marked on a paper “master map,” tweaked every year by Laz, that runners have to copy onto their own maps. “If they don’t exactly match the master map that’s their own problem,” Laz says in the doc. A troll through and through. The route leads them through untamed forests, across rivers, through the drainage pipe of an active prison, up impossibly steep mountains covered in burs that leave people’s legs a bloody mess. The weather is unpredictable: winds, hail, sleet, snow, ice, rain, extreme heat. The first two loops are done clockwise, the second two are done counterclockwise, and for the final loop the runners are split up going alternating directions.

There is no prize for winning the Barkley. There are no corporate sponsors, no loudspeakers announcing finish times, no spectators beyond the spare crews of the racers themselves. In its first 36 years, only 15 of its nearly 1,500 starters have finished it. Most years, no one even gets to the fifth loop.

Watching a 60-hour ultramarathon condensed into a 90-minute film of course obscures the full scope of the experience. As the race lingered in my mind, I started reading blogs and race reports by people who had competed at the Barkley (like this one by John Kelly or this one by John Fegyveresi). I wanted details. I needed to understand what it was like to finish a grueling marathon through hellish terrain and then agree to do it again and again, even when it was dark and raining and you knew you’d get lost, even when you hadn’t slept in two days and you could barely walk from the blisters and were starting to hallucinate. What could possibly compel you forward in those moments? How could a person endure that level of misery voluntarily? Did I mention that the Barkley course has 12,000 feet of climb and 12,000 feet of descent, which is the equivalent of climbing and descending Mount Everest twice?

You might assume these people are so elite that something like this is manageable for them, but it’s not. The Barkley is unspeakably difficult and impossible to train for. Laz describes it as “right at the limit of what people can do.” Barkley alumnus John “Fegy” Fegyveresi ran the 130-mile Badwater Ultramarathon through Death Valley’s 110-degree heat with a full-on stomach virus (vomiting, shitting everywhere) and still said the Barkley was harder “without question, there's no comparison.” The last time someone finished the Barkley was in 2017, and when the guy who did it, John Kelly, approached the finish line, he was so far gone mentally that he didn’t know where he was. “In my mind’s eye, this final section had been a relaxed victory march down the mountain,” he wrote. “[R]eality was vastly different. By that point I was losing it. Again I felt like I would fall asleep if I blinked for too long, and even awake I didn’t feel like I was awake, or that anything was real.” (Both Johns reported forgetting, in loop five, that they were racing at all.)

“You can’t accomplish anything without the possibility of failure,” Laz states in the documentary. The specter of quitting is an integral aspect of the Barkley; it is, after all, the fate of most participants. And yet there is little shame in it. The quitters become the support systems of the remaining runners, who aren’t so much competing with each other as helping each other get as far as possible. “Sometimes when something defeats us, we feel a need to go back and prove something to ourselves, I guess,” one guy said in an interview, minutes after he dropped out. “I don’t feel that way about this. I gave everything I have and it wasn’t enough and I’m ok with that.” Many race reports I read echoed this idea—that the attempt alone was the victory.

This may be why it’s more touching to watch average people run the New York City marathon than to see the elite runners who sprint smoothly by, as impressive and inspiring as they may be. That’s not to say it’s easy for them, but the possibility of failure looms larger for the rest. “People have their own concepts of success and failure,” Laz says of the participants. “[B]y the time they’ve been through the ordeal, [they] really aren’t concerned about how other people evaluate their performance. They make their own judgments about success and failure.”

Kelly has attempted the Barkley five times. While he’s ostensibly motivated by conquering it, his writing suggests it’s not actually about that. “I just couldn’t ‘feel’ anything,” he wrote, of the days following his first and only completed Barkley. “It never felt like a Pyrrhic victory (ed note: great reference), but at times it did feel hollow. Is it the pursuit of goals or the achievement of them that is most rewarding?”

In one of my favorite essays about running by the poet Devin Kelly, he refers to running as an “impatient dance with patience.” Through his own mistakes he’s learned that caring only about the finish—of the satisfaction, or the glory—and failing to enjoy being “out there,” saps the whole endeavor of its meaning. He quotes the Suzanne Buffam poem “On Duration”: “To cross an ocean / You must love the ocean / Before you love the far shore.” The people at Barkley seem to understand this on a fundamental level. At first glance they may seem nuts, ego-driven, out to prove something arbitrary. But their actions don’t really bear that out. The possibility of finishing might be a motivator, but the attempt to finish is the point.

I think it matters that none of my ruminations about the Barkley have concerned the finish line, but the moments the runners, haggard as hell, decided to keep going, or else said resolutely, without judgment, that they were done, then became supporters themselves. I know there’s something a bit on the nose about that, as far as inspiration goes, but it’s nice to be reminded that those moments—continuing on, or else changing course—are the ones that linger. The outcome is all but irrelevant.

My favorite article I read last week was “Mental Health Is Political,” by Danielle Carr for The New York Times, about the medicalization of mental health and who it benefits. Last week’s 15 things also included, among other things, my new winter coat, a great autumnal album, a game I was sad to beat and another I’m struggling through. The rec of the week was books that are hard to put down. Really great list going!

Last week for the podcast, I watched the Selena Gomez doc for you (and had big thoughts). Coming up, Avi and Chris are back to do a full Love Is Blind S3 debrief (maybe you remember our classic Ultimatum ep). Hard-hitting stuff.

Hope you have a nice Sunday!

Haley