The other day, while FaceTiming my mom, I inspected the baby monitor for signs of distress. The baby wasn’t crying, but she wasn’t quite asleep either. “You should put that away,” my mom said, “She’s fine!” Back in her day, she would just listen through the walls. If we were quiet, she assumed we were asleep. I knew she was right. I’ve known for a while—more information is not always better. My eyebrows furrowed as I zoomed in on the baby’s left eye, forgetting my mom was there.

Did you know there’s a tiny sock you can place on your baby’s foot that connects to your phone and tells you, at all times, whether your baby is breathing? Instead of holding the monitor an inch from your nose in search of proof of life—sometimes the matter of a couple undulating pixels—you can simply check the app. There you can find even more data than you need: your baby’s pulse, her oxygen levels, where she happens to be in her sleep cycle, and more. This will buy you peace of mind for the relatively low cost of $299—at least that’s what you’ll tell yourself when you enter your credit card number with one eye closed at 2 o’clock in the morning.

It only took one month of motherhood for me to transition from making fun of the existence of the Owlet Dream Sock to secretly checking its price. But I knew deep down that I didn’t need it, for the same reason I don’t need to bring the baby monitor into the bathroom with me when I pee, or record every detail of her every feeding on my phone. What I need is something far more existential: to learn to not know. This would cost me about $300 fewer American dollars.

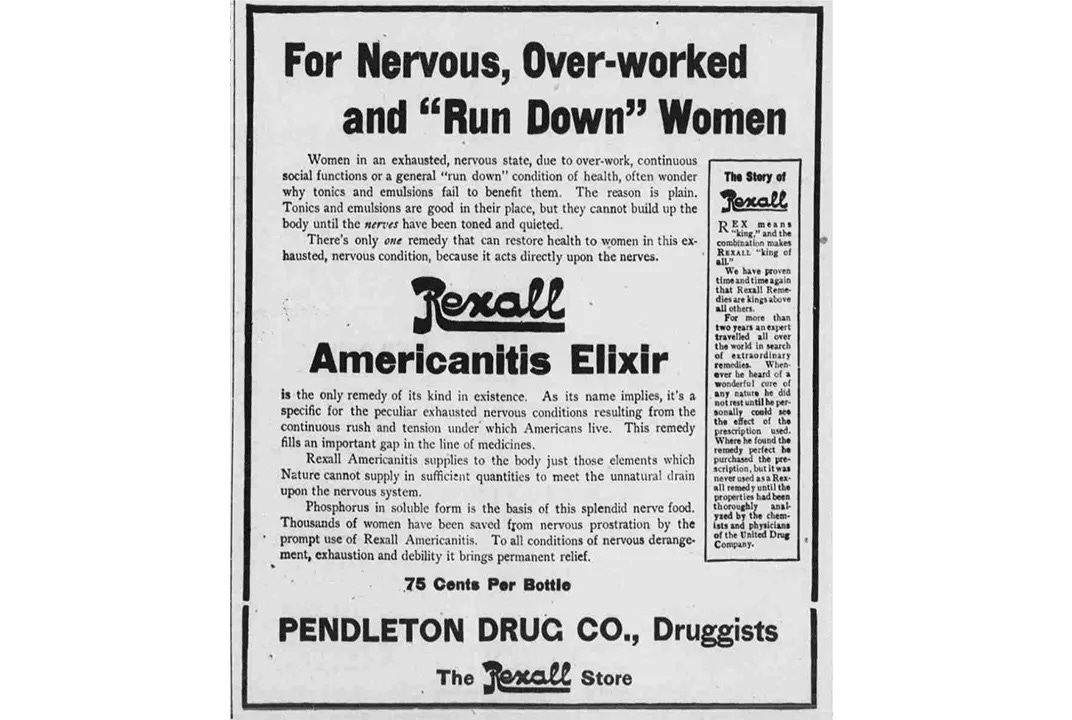

In Lauren Oyler’s essay about anxiety last week, she referenced a late 19th century diagnosis known as Americanitis, which described “the high-strung, nervous, active temperament of the American people.” Whether incited by advances in technology (causing loss of sleep, excessive worry) or capitalism (causing long work days, fast pace of life), the result was, according to experts of the time, a rattled population unable to relax. A black mirror of the American dream, Americanitis took the same ideas favored by patriots and recast them as depressing. Here is the land of possibilities—so vast in scale you’ll forever be unsatisfied!

Sadly the term fell out of favor during the Great Depression, but I mention it in the context of the smart sock because I think it trades on a critical aspect of our national sickness: an unyielding belief in technology’s ability to allay our suffering. I don’t mean technology in the strict Silicon Valley sense, but innovation generally. Loneliness, ugliness, aging, death—there’s no unavoidable problem we aren’t trying to avoid, no question we aren’t trying to answer. To accept things as they are would seem to betray our American destiny.

Obviously this bullishness has some positive impacts; people with dreams immigrate here for a reason, at least they used to. But this sense that no improvement is beyond our grasp also has a way of warping our worldview. What can’t we buy with enough money, figure out with the right search query, achieve with enough hard work? The potential is endless. Nothing is enough. Maybe some parents find the sock useful, but “there’s little evidence that alarm-based monitoring wards off SIDS.” If I had to guess, what the sock is most effective at keeping alive is the parental hope that more oversight will always and necessarily protect your kid from harm.

I still want it, just a little. I often forget my anxiety isn’t caused by a lack of answers to my swirl of questions, but the swirl itself. I frequently operate as if one more Google search will solve everything, circling around and around the internet, mercifully sedated by information I probably don’t need and will forget next week. Sometimes, I really do find the answer I’m looking for, and then I’ll stop, smug and satisfied. The problem with feeding the beast is it’s not the same as killing it. Soon enough, I’m hungry again.

Recently I learned about Lacan’s concept of jouissance, which I’ve come to understand as pleasure that becomes so intense it’s hard to distinguish from pain. I’m fairly certain this describes the high of answering anxiety’s biggest questions: binging on information, hoarding social validation, buying stuff, so much stuff, crafting five-year plans. There are infinite resources available to quell our voids. We can quell them forever, packing our perforated souls with tiny bits of information and expired creams and half-filled planners. Will this feel extremely good or extremely bad?

Before I got pregnant or had a baby, I was pretty effective at addressing my anxiety this way. Making plans when I felt friendless, organizing drawers when I felt scared, washing my hair when I felt ugly. Maybe I wasn’t always addressing the root causes, but I felt productive anyway. The particulars of parenthood, however, render this approach absurd, because the only thing “to do” about parental anxiety is turn your home into a lab, your baby into a test subject, and your life into an unceasing struggle against the natural order of things, which is no order at all. Some people do this, of course. I’m sure they’ve been rewarded with perfect, tranquil lives.

The other day I saw a tweet: a photo of a group of older men sitting outside a cafe around a wooden table, clearly not in America. Worn-in loafers, baggy khakis, cups strewn around the table. They look like they’ve been there all day, like they aren’t tracking breaths on an app, like they’re living the questions, per the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. That people like that have no worries is, I think, one of those fundamentally American misunderstandings. Contentment, acceptance, is something different, and harder-earned. “This is all I truly want,” one person wrote, probably from their smartphone. “I yearn for this life.”

My favorite article I read last week was Oyler’s essay I mentioned above. Last Friday’s 15 things also included my new morning activity, my favorite not-fancy hand soap, my new desk accessory, and more. I also asked for your Kate Middleton theories, because I needed them. My favorite is that she got bangs and is hiding out because they’re terrible.

Have a nice Sunday,

Haley