Good morning!

It’s Dear Baby week meaning I’ll be answering five reader questions for my paying subscribers and sharing one with you for free. The questions are:

I’m 22 and feel eager to be older than I am. How do I stop cringing at my own mistakes?

After 5 years in HR, do you have any behind-the-scenes secrets to share?

How do you deal with bad or difficult writing days?

I recently received some disappointing career news. Should I tell myself everything happens for a reason? Is there another way?

Can you talk about the feeling of it being “too late"? I know logistically it isn't true but the feeling is overwhelming.

Naturally I wrote a full essay for each one because I’m a masochist. But they were such good questions I couldn’t help it. Thank you as always for writing in! Today I’m going to share my answer to #3, about writer’s block. It’s not quite as existential as the others but I did make a flowchart and maybe you’ll find that more immediately useful.

3. On Writer’s Block

“How do you deal with difficult writing days? How do you know when to give up on an idea? I'm trying really hard to be consistent with my own writing project but some days I find it impossible to come up with something good or valuable. I adore your writing and this newsletter and I just want to know how you face those challenging days when ideas feel stupid and words don't flow right.”

I’m sorry you’re struggling with your project! The first thing I will say is everyone’s relationship with writing (or any kind of creative work) is specific to them. While I do think some writing aphorisms are universal, like the idea that you can’t get better without lots of practice, I find that many of them—like “write every day” or “start early” or “shitty first drafts”—don’t account for the infinite differences across personalities, strengths, resources, general life situations, etc. In my view, the idea that what works for one famous writer will work for others is born of the same myopic delusion that inspires celebrities to tell us to follow our dreams. So before I tell you what I do, I’d encourage you to treat your own experiences as the best data for building a framework for how and when you work best. Think about times you’ve been more motivated, energized, and able to follow through and times you weren’t. What differentiates them? Or how about times you dragged your feet but ended up pulling through—what helped you? What definitely didn’t?

For me, dealing with a bad writing day is all about diagnosis. There was a time in my writing life when I conflated writer’s block with just not trying hard enough, and another era when I conflated it with being burned out, and another when I was sure that every snag could be fixed with an outline or a phone call with a writer friend, but none of these were always true. Writing can be hard for different reasons—being tired, aimless, afraid, confused, intimidated—but often the feelings present similarly: we feel frozen, want to procrastinate, do anything but write. One of the biggest challenges for me has been learning how to suss out the differences between different blocks, and thus understand how best to respond to them. I still make mistakes sometimes, but I’m getting better at it as time goes on, and you will too.

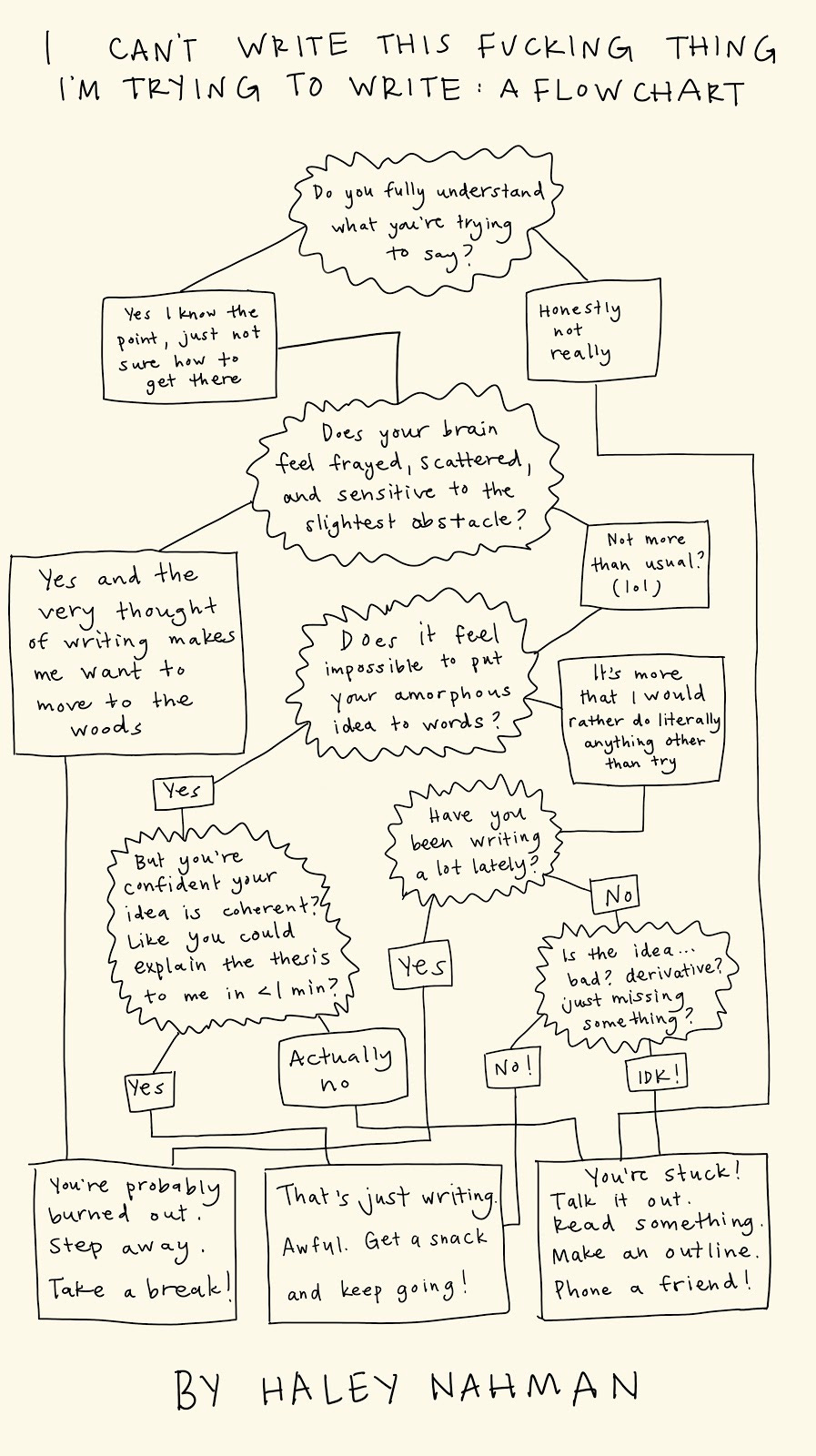

Here is a loose visual representation I made for you re: how I deal with bad writing days:

As you can see I place a lot of emphasis on the quality and clarity of the idea. This is something I learned a lot through working as a professional writer and editor, where there is no way out of writer’s block but through. I found that oftentimes when I was struggling with a piece, as a writer or as an editor, the problem was foundational: the initial idea was not perfectly coherent. It might have sounded good in pitch form, or compelling as a headline, but drawn out it didn’t track. This is why writing is sometimes harder than we expect it to be; we think we have tons of good ideas but fail to account for the fact that it’s much easier to toss off a thought in conversation or on Twitter than it is to actually communicate it thoroughly or artfully. This happens to me all the time, and sometimes it takes trying to write it out to realize. If you find yourself there, try explaining your idea to a friend, or make an outline, or sum up your idea with a title and thesis statement. Crystalizing your idea can free up some of your headspace.

But sometimes the ideas are good and the words still don’t come, or the very process of clarifying the idea feels too mentally taxing. Having to work through burnout because you’re on a deadline or have no time is a very painful experience. To be honest, I’ve been going through that with this very newsletter. After writing so many intense essays over the past months, writing this much this week has been really hard. I know it hasn’t led to better work and I can only imagine the ripple effects it will have next week.

You can swap in a variety of external or personal problems for burnout on the chart—mental health, the conditions of your life, a pandemic. Sometimes your inability to express yourself creatively isn’t something you can fix through individual action. Writing may seem like a widely accessible hobby, but it takes a surprising amount of time and energy that not everyone has. I can write as much as I do because I have three full days every week just to write, not including the weekend. Which means that if I wake up on the first day and feel totally incapable of writing, I can choose to do something else that day and revisit it the next. I’ve never had that kind of flexibility before, and now that I do, I understand it’s the ultimate privilege—one our work culture often doesn’t account for, let alone encourage. I protect that time even when it means sacrificing more money, which sometimes feels counter to my instincts. I also can comfortably pay my bills and generally feel supported in my work, which isn’t something many writers have, and I still get blocked and burned out. We live in a mentally taxing time and writing itself is mentally taxing, but it can also be deeply satisfying, so you just need to check in on where you are.

All this is to say: It’s highly personal and also societally informed. Learning about yourself (when you work best, how to diagnose your block, when you’re lying to yourself, etc) will help a lot, but understanding what external pressures exist for you will paint a fuller picture. Modern life in the West has done so much harm to creative pursuits—by working everyone to the bone, by making commodification the only goal, by glorifying the hustle—that blaming only yourself for struggling to keep up is not only unhelpfully harsh, but inaccurate.

On my podcast this week I’ve invited on one of my friends and mentors, Verena von Pfetten, cofounder of Gossamer magazine, to talk through all the questions from new angles. Our conversation was so good and her answers were so wise, I’m really excited to drop it on Tuesday. If you’d like to support Maybe Baby by paying $5/month and gaining access to all this stuff, you can click here:

Then you’ll have the option to go ham on the full archive, including this week’s column.

Thanks so much for being here either way!

Haley

This month a portion of subscriber proceeds will be redistributed to GlobalGiving Coronavirus Relief Fund, a non-profit focused on equitable vaccine distribution and getting resources to those made especially vulnerable by the pandemic.

Give me feedback • Subscribe • Request a free subscription • Ask Dear Baby a question