#50: Beautiful dining chairs

Maybe Baby is a free Sunday newsletter. If you love it, consider supporting it financially. For $5/mo, you’ll gain access to my monthly Q&A column, Dear Baby, as well as my weekly podcast. Maybe Baby is reader-supported, hence the lack of ads and sponsors. Thank you!

Good morning,

Life on Earth continues to be wonderful and awful, and lately it’s really pulling out all the stops to prove it’s both. Hope you’ve had the chance to get outside a little to see the trees bloom. Meanwhile I’ve been running around my new apartment like it’s on fire. I’ve possibly lost my mind a little, but not in a bad way. I’m actually feeling very lucky.

Sick

I’m sitting in the backyard of an Italian coffee shop, trying to think about anything other than dining chairs and the decline of America. The air smells like coffee and toast and wet gravel, which is helping. I am writing this by hand in a notebook on a wobbly wooden table. My left hand hurts from being out of practice. I am trying to be here—which is to say, somewhere other than inside my intriguingly unfinished apartment and in front of the 23 tabs I have open on my laptop. I need to be present for once in the spring of 2021. And yet four inches to my right, my phone begs for my attention: push notifications that my favorite vintage resellers are posting new inventory, a push notification from the New York Times about the vaccine recall, a text from my friend Michelle: “It’s 9:45 and I’m already looking at pillows. Why.”

Michelle and I have the same sickness, are getting in the same cliche arguments with our partners about the definition of need. We text each other about this several times a day, distracting ourselves from everything except maximizing the space in our Brooklyn apartments. She recently bought the wrong dining chairs: They are metal and slatted and, paired with her dining table, also metal and slatted with glass on top, her apartment now resembles a weather-proof patio. Friday, 6:41pm: “Our chairs came and I’m mad we didn’t spend more money on them.” Saturday, 11:04am: “Ugh think I hate them I don’t know!” Sunday, 3:16pm: “We’ve decided to sell the chairs.” I agree the chairs are not right. Of course, we could ask ourselves why chairs need to be “right,” but we are too busy thinking about which chairs qualify. What both of us actually want are wooden stacking chairs by Bruno Rey. Unfortunately they are $450 a piece, and in the budget I made last month, I allotted $200 for dining chairs total.

“I’ve banned myself from thinking about decor today,” I reply to Michelle’s text about pillows, probably lying.

Avi keeps gently suggesting I take a breather. When he says this I bristle. I don’t want to take a breather, I tell him, I’m fine! Of course he’s right. I am making myself anxious from and for nothing, like spontaneous combustion. But I wish I could adequately communicate that despite my crazed eyes and inability to stop measuring random surfaces in our apartment that it’s easier to obsess over decor than almost anything else in the world. I am busy, distracted, occupied, dreaming. When I am reading reviews about knife magnets I am not reading the news. When I am looking for an extendable shoe rack I am not looking for a reason to go on. This is probably the point of capitalism.

Wasting disease

Consumption (noun): the leading cause of death in the United States at the turn of the 20th century, also known as tuberculosis. Eula Biss pointed out the connection in her book Having and Being Had: consumption as wasting disease and then, later, as wasting disease. “In the furniture stores we visit, I’m filled with a strange unspecific desire,” she writes. “I want everything and nothing. The soft colours of the rugs, the warm wood grains, the brass and glass of the lamps all seem to suggest that the stores are filled with beautiful things, but when I look at any one thing I don’t find it beautiful.” I know what she means—the way desire is more alluring as a mosaic of hypotheticals; to want everything over something specific, which requires choosing, which requires giving the rest up. Better to want it all and not be disappointed.

I left the backyard of the Italian coffee shop. When I got home I installed shelves on the inside of my bathroom cabinet doors. It doesn’t matter whether or not that counts as “thinking about decor,” as I also spent 30 minutes looking for a desk on Etsy somewhere in-between, so the deal is off. The desk needs to be long and narrow, or is it shallow, I searched both, and it needs to be beautiful, although I am not yet sure how. It could be a beige, laminate waterfall desk from the 80s, but those are really having a moment, so that’s probably not the right choice. Buying something because it’s having a moment and has thus infiltrated your brain usually means owning something, one day, that once had a moment and is now being reproduced for a fraction of the price at Target, inverting its original appeal. But what if I genuinely like the look of it? Please apply this to: tiled tables, checkerboard rugs, colorful striped towels, pillows shaped like clouds, candles shaped like tumors.

“Maybe the problem,” Avi said to me last week, “is you have trouble expressing the value of these things to me. I know it’s intangible and I want to understand, but it’s not something I’ve ever been tuned into.” I had just shown him the Bruno Rey chairs—for research, of course. “My friends do not invest in these things the way your friends do,” he then said, and I wondered why I immediately thought his friends sounded like the right ones, and why I couldn’t express the value of things I purportedly wanted. Did it matter that we would enjoy looking at our dining chairs? Did it matter if they were “an investment”? The pea-green credenza I enthusiastically bought off Craigslist in 2019 and have since inexplicably disowned has its doubts. Did I ever really love it? I forget. Maybe the problem is I’ve lost track of the difference between what I like, what is novel, and what is cool. The problem could be a lot of things, and is.

Arguments for caring about your home decor...I write in my notebook.

-Physical spaces shape thoughts, behavior, and emotions

-If your home recharges rather than drains you, you’ll be a more present and generous person

I pause.

-It’s fun!

And then: Arguments against caring about home decor...

-It’s expensive (and at times wasteful)

-It can be more concerned with identity performance and consumerism than genuine experience of the home

-It tricks you into thinking it’s more important than other, more important things

A beautiful chair

What purpose, exactly, does a beautiful chair serve? For one, it is a chair, so you can sit on it. You could do this in an ugly chair, but a beautiful chair will make you feel good, or like the best version of yourself, every time you look at it (until you get used to it or grow to hate it). Perhaps the chair is well-made and comfortable, which means you won’t have to replace it soon, and that’s good, even moral. The beautiful chair could be posted on social media and incite the envy of others, which might gain you a little extra social capital, sure to impact your long-term happiness almost not at all. The beautiful chair could be used to signal to other people with good taste that you have something in common. Conversely, it could be beautiful only to you, which could make you stand out. The beautiful chair could make you sit up extra tall. You could take the beautiful chair outside on a sunny day and be “glad among the trees,” a la Mary Oliver, which would perhaps betray a misunderstanding of the poem. You could sell the beautiful chair for rent money. You could call the beautiful chair “art,” even if the real reason you bought it wasn’t because of what the chair said but because of what you thought the chair might say about you.

I must be missing something.

“What do you think we’re really after?” I text Michelle. “Re: decorating mania.”

Michelle: “The first thing that comes to mind is that it’s my first place with a partner and I really want to build something with him that feels like a home and an adult life separate from the home I grew up in.”

Me: “That totally makes sense. But then I guess the next question is why do we define adulthood through things? (I’m not saying we shouldn’t, just curious)”

Me: “Or another question might be, what value is there in feeling like an adult? Maybe it’s a stabilizing force, but it’s intangible, so we rely on what we can see to reinforce it, believing more structure will make us feel safer, less vulnerable to the whims of youth, more self-assured?”

Me: “Whether that’s actually what happens when you buy home decor, up for debate”

Me: “Lol”

Michelle does not reply because she has class. (She is a teacher.)

Michelle and I are in our thirties. We are adults. To feel like an adult is something else, though—a condition entirely separate from age. To feel like an adult is to feel unlike a child, who might be defined by naiveté, playfulness, and reliance on others. An adult is wise, principled, and independent. An adult decorates. An adult invests. An adult does not buy a rug and then hate it a year later, or fail to buy a rug at all. An adult knows what they like and what they need. An adult’s taste and values are reflected in their things and in their home. This is what advertisements have been trying to tell us.

The beautiful chair, then, makes us feel better. The beautiful chair reminds us that we are not so vulnerable, fickle, and flighty as we once were. The beautiful chair costs more money than perhaps that ephemeral sentiment is worth. The beautiful chair is merely furniture. In the event of the apocalypse, assuming it’s made of a flammable material, the beautiful chair could be burned for warmth.

Signals

One thing decor does fairly well is signal what we care about. Sometimes, it signals what we want people to think we care about, which is different. In his book Against Everything, social critic Mark Grief examines the early 2000s phenomenon known as the hipster. “The hipster is that person … who in fact aligns himself both with rebel subculture and with the dominant class, and thus opens up a poisonous conduit between the two.” This might have been why hipsters got a bad rap—by caring about being seen as cool, they became precisely what they purportedly loathed: try-hards. They became a contradiction. A $50 t-shirt that says I DON’T CARE WHAT YOU THINK.

The perfect modern adaption of the hipster might be James McElroy’s description of today’s bureaucrats:

“Professionals today would never self-identify as bureaucrats. Product managers at Google might have sleeve tattoos or purple hair. They might describe themselves as ‘creators’ or ‘creatives.’ They might characterize their hobbies as entrepreneurial ‘side hustles.’ But their actual day-in, day-out work involves the coordination of various teams and resources across a large organization based on established administrative procedures. That’s a bureaucrat.”

Apply the parallels generously: hair designed to look slept in, jackets that come pre-ripped, anti-capitalist merch, quilts sold on Urban Outfitters under the moniker “Bohemian.” If you try to make your apartment authentically Bohemian, haven’t you already failed? If you try to be authentically anything, haven’t you already failed? You can only be authentic by accident. Marketing makes phonies out of all of us.

“The rebel consumer,” Grief writes, “is the person who, adopting the rhetoric but not the politics of the counterculture, convinces himself that buying the right mass products individualizes him as transgressive. … [H]ipsterism did not make an avant-garde; it made communities of early adopters.” A value system based on speed and consumerist symbolism. Maybe that’s why I’ve been so impatient, scrolling through websites like I’m being chased.

Michelle gets back to me: “I absolutely love the sentiment of being vulnerable to the whims of youth.” New text: “Which is ironically the very thing that makes us feel alive but we feel we need to suppress.” New text: “my students also were advocating for adult playgrounds today.” New text: “like actual playgrounds for adults. and I’m like, actually? Yes.” New text: “maybe we’re just designing our playgrounds!” I heart the messages.

Hanging in my kitchen are two gray kitchen towels. Every time I look at the towels, I think, those towels are hideous. They do not, per Konmari, “spark joy.” Sometimes I imagine a friend entering my house, noting the towels, and misunderstanding me as the type of person who likes the towels. I hate this idea as much as I hate what this fear says about me as much as I hate the towels. And yet, at some point, I purchased them—although I can’t recall when—and ostensibly did not harbor this same resentment. So now they hang in my kitchen, gray like wet gravel, as a reminder that I do not know myself. That I have and will continue to change in unpredictable ways. It seems like a worthy reminder, but who wants to be reminded of that?

1. “Hope Is a Discipline,” an interview with Mariame Kaba on The Intercepted podcast. You can listen or read the transcript here. After the horrifying murders of Daunte Wright and Adam Toledo by police came to light during the Derek Chauvin trial last week, abolition continues to be an urgent idea. If you want to think more about abolition or are new to it, I highly recommend Mariame Kaba’s teachings.

“The killing hasn’t stopped. The harassment hasn’t stopped. The injuries haven’t stopped. And yeah, sure, Derek Chauvin, maybe he’s convicted, maybe he’s not. But we’re still gonna see 1,000 people killed every single year. That just should tell you something about the futility of these [convictions]. … It’s really impossible for non-oppressive policing to exist in a fundamentally oppressive and unjust society.”

I also suggest “How America Became Over-Policed,” by Mychal Denzel Smith; “You Are Already an Abolitionist” by Benji Hart; and “Is Prison Necessary? Ruth Wilson Gilmore Might Change Your Mind,” by Rachel Kushner—all resources I found very helpful in my own education. If you’d prefer a book, Kaba’s newly published We Do This ‘Till We Free Us collects her many essays and interviews on the topic of PIC abolition.

Ps. I recently learned that you can save podcast episodes to Pocket, if you want to save the Mariame Kaba interview for later.

2. “The Root of All Cruelty?” an interesting piece by Paul Bloom for the New Yorker about what we actually mean when we peg certain behavior as “dehumanizing.”(It’s not what you think.)

3. The Wikipedia page for “The Top Five Regrets of the Dying,” shared of course by my neurotic brother.

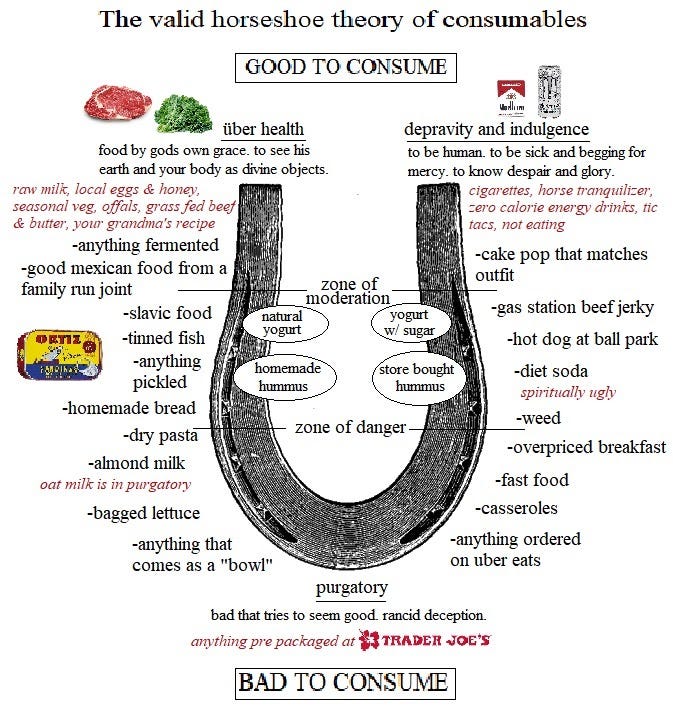

4. “The horseshoe theory of consumables,” also shared by my brother. Who made this??? Lol

5. “Two Lives, Simultaneous and Perfect,” an essay about filmmaker Éric Rohmer by Becca Rothfeld for Cabinet Magazine. To be honest I didn’t know who this filmmaker was, or who Becca Rothfeld was, or what Cabinet Magazine was, and I still loved this essay.

6. Troye Sivan’s home tour with Architectural Digest. Can you imagine living in a house like this at 25?? Or...ever?

7. “I, Phone,” an essay by Choire Sicha for the New York Review of Books that is kind of a review of Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts but is also so much more.

8. The chicest cat paraphernalia I’ve ever seen on Happy & Polly.

9. The trailer for Ziwe’s new show on Showtime, which looks good.

10. Hypernormalisation, a 2016 documentary by Adam Curtis that’s on YouTube in its entirety. Still haven’t seen his new one but this one took me literally four sittings to get through so I need a break now.

11. This Bennydrama TikTok, but really any Bennydrama TikTok.

12. “The Best Friends Can Do Nothing for You,” a piece in The Atlantic by Arthur Brooks about why friendships based on mutual benefit (in terms of career, status, clout, etc) don’t feel as fulfilling as friendships that do nothing for you. Lots of people in New York probably need to read this.

13. “Time, Tarkovsky And The Pandemic,” a video essay by Nerdwriter on how our perception of time skewed throughout the pandemic. Or more broadly, an explanation behind why “the days are long and the years are short.”

14. This excerpt from the journal of the poet May Sarton: “Sometimes one has simply to endure a period of depression for what it may hold of illumination if one can live through it, attentive to what it exposes or demands.”

15. And to end on a high note: “The Quiet Horrors of Cally Gingrich,” a recent issue of Ashley Feinberg’s perfectly unhinged newsletter, Trashburg. There’s truly nobody like Ashley Feinberg, singular in her dedication to unpacking mysterious, right-wing internet ephemera.

On the podcast this week: a conversation about Stuff

This week I invited my friend Connie Wang, the executive editor of Refinery29, on the podcast to talk about consumerism: the difference between having taste and being on trend, whether it’s okay to define yourself by your stuff, and the limits of prioritizing our consumer choices in the first place. We have had very parallel journeys as consumers, so it was fun to talk to someone who spends all day thinking, writing, and editing about the human relationship to style (in all its permutations).

Thanks for reading!

Haley

P.s. If you didn’t have a chance to take my reader survey last week and would still like your perspective included, you can still take it here. Thank you to everyone who did!

P.s.s. After groveling all over my Instagram about Cool Hand Movers, the local family-owned business Avi and I hired to help us move, they sweetly wanted to offer my subscribers a discount!! If/when you get a quote, say you heard about Cool Hand from me and you’ll get 10% off.

This month a portion of subscriber proceeds will be redistributed to CAAV, an organization working to build grassroots community power across diverse poor and working class Asian immigrant and refugee communities in New York City.

Give me feedback • Subscribe • Request a free subscription • Ask Dear Baby a question