#58: What’s up with Instagram?

Maybe Baby is a free Sunday newsletter. If you love it, consider supporting it financially. For $5/mo, you’ll gain access to my monthly Q&A column, Dear Baby, as well as my weekly podcast. Maybe Baby is reader-supported, hence the lack of ads and sponsors. Thank you!

Good morning!

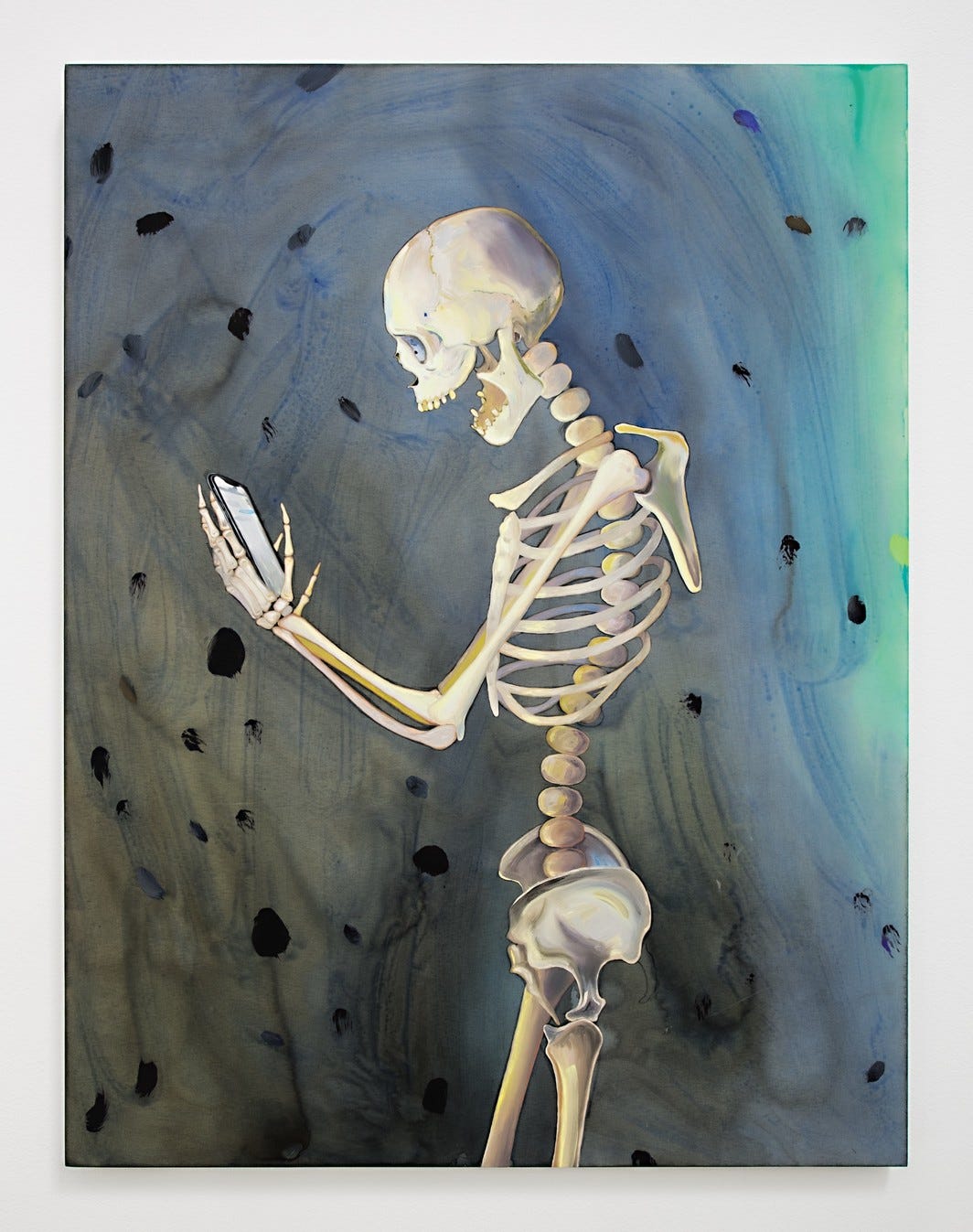

The teens say Instagram is dying, or dead, and I’m finally starting to feel it. I haven’t posted to my feed in nearly six weeks, and in that time I’ve amassed more postable content than I did the entire year before. I’m socializing, I’m wearing full outfits, my hair’s looking fluffy and washed, and my desire to share it has been eclipsed by my desire to never share anything again. Occasionally I’ll feel the urge, and then I’ll ask myself: What’s the point? And the answer never comes. My feed barely entertains me. I scroll it only to avoid doing something else. And while it’s true I go through these phases often, I can also sense that my relationship with the app has shifted fundamentally over the past 12 months. After years of heeding its stupid little call, the siren song of Instagram has quieted to a dull thrum. I notice it like I notice music in another room.

The toxicity of Instagram is common knowledge. Nearly everyone I know on the app at least partially loathes it, and every major news outlet has run countless stories about why. It’s been on the decline for a while now—reputationally moreso than financially—but I suspect there’s more to it than the frequently trotted out culprits: the fraudulence, the algorithm, the depressing time-suck of it all. Because no matter how often or creatively we try to reckon with these things, Instagram only gets worse. And I think that betrays something important about the possibilities of online social platforms in the first place.

When I say social platforms I mean those organized around personal, expressive accounts, versus anonymous forums dedicated to niche topics like My Little Pony or chronic pain. I think the distinction is important, because there’s something inherently performative about building a profile, sharing a selection of photos and videos you’ve taken, and getting paid in likes and views. It’s not hard to see why Instagram became famous for being fake: It’s Instagram versus reality, as the saying goes. We may have originally conceived of our roles as real people sharing parts of our real lives, but we’ve over time become entertainers, performing ourselves (or some version of ourselves) for digital claps. Even TikTok, which has successfully avoided some of the pitfalls of Instagram, suffers the same perception gap: “I think the biggest misconception is that TikTok is this ephemeral, fun, authentic place where everyone can be themselves,” reporter Shelly Banjo said to Rebecca Jennings in an interview for VOX. “These creators, as you know, work so hard. It’s their job; they will sit there for hours and hours making 15-second videos that appear fun and authentic.”

But Instagram, more than TikTok, is hamstrung by its own goal: to reflect our lives. And so our response to this collective reckoning around its fraudulence has been to invite more aspects of “real life” into them: more vulnerability, more activism, more real-talk. The effect has been surreal: crying selfies interspersed with FaceTuned ones; public diary entries written beneath aesthetic tablescapes; political rants next to tagged outfits; Notes app apologies between party photos; calls for authenticity from faceless corporations. We all contain multitudes, contradict ourselves, are constantly evolving, but I don’t think the mishmash of intention that’s become commonplace in our feeds reflects the human condition as much as our neuroses. And I think it’s made online spaces all the more unbearable and barbarous, because it’s not as authentic as it portends to be. We’re still performing, just more dynamically. In some cases, sneakily. A paradox.

Maybe our biggest mistake was to assume that authenticity online was our biggest problem. I think it’s led us down a path of denial about what these platforms can really do for us, or express about ourselves. At least, it has for me. What I’ve been wondering is: How bad is inauthenticity, really? I’m inauthentic all the time: When I feign confidence at a new job; when someone sends me a meme I’ve already seen or gives me a gift I don’t want; when I get up instead of (my true passion) lay down. Performance is part of life. In its best moments, it can be an act of self-creation. “Fake it ‘till you make it” is a cliche because it works. But what most of us understand about offline performance is that it can also inhibit genuine connection—that a life subsumed by it would be an empty one. This may offer us a hint as to why online spaces remain, on balance, uncanny and draining, no matter how hard we try to make them otherwise.

My favorite social media accounts are not those most effective at transmitting authenticity. In fact, they’re the opposite: the ones that embrace performance as a key element, or have a different purpose altogether, like education or memes or videos of dogs balancing rice cakes on their heads. Forms of expression that are explicitly tailored to the unique and alien value prop of the internet. Imagine what these spaces might feel like if our obsession with authenticity dropped, and our understanding of Instagram—or any social media platform—as a reflection of our beliefs, lives, personalities, and thoughts dissolved altogether. Maybe then the point of posting would not be, as Max Read once put it, “to call attention to ourselves,” full stop, but to call attention to something else—perhaps an aspect of our interests more attuned to the medium. What if we understood we could never know or be known through posting? Might we feel less pressure? Expect less of other people? Feel less entitled to them? Less angry?

Some time last year I decided to stop expressing my political beliefs on Instagram. Part of this was inspired by watching Adam Curtis’s documentary Hypernormalisation, where he points out that the most measurable impact of posting is the increase of power of those who own the platforms, like Mark Zuckerberg. That in fact a belief in the singular impact of posting might keep us politically docile. “We’re in this very funny paradoxical moment in history,” Curtis said in a recent interview with Idler, “which is full of moments of dynamic hysteria, yet everything always remains the same. We get this wave of hysteria—angry people click more!—and those clicks feed the systems and nothing changes.” My view may be a bit softer, but I think the most impactful movements still happen offline. Or, at the very least, use social media predominantly as a means for accelerated collectivism (#MeToo) or organizing (BLM). In the case of my personal account, otherwise filled with outfits and photos of my cat, posting political content feels less impactful. I feel much more activated in other areas of my life.

I’ve at times felt overwhelmed by how poorly my social accounts communicate who I am. I think I used to find this motivating—post through it! be seen!—sometimes even found it fun. But I’m becoming less energized by trying to prove the unprovable. Even defeated. These media are simply inadequate at expressing humanity. Each legacy app’s insistence on its ability to connect us, and our absorption of that message, has created a hostile social landscape where bitterness flourishes far more readily than intimacy and understanding, the real-life anchors of connection. What’s more, these frameworks violently simplify us, betraying one of our most fundamental needs: to be known by our communities. In the Idler interview, Curtis goes on to say that what these online social models fail to capture, and will always fail to capture, is the mysterious and romantic side of life:

“Real intelligence is being able to walk through an incredibly crowded street on a busy evening, nimbly, when you don’t even think about it, while at the same time recalling memories and replaying things in your brain. What I’m saying is that human beings have been reduced to a very simplified version of themselves, which they’ve accepted, in order to fit into this machine model, both of society and the internet. But we are extraordinary and we can do extraordinary things. We are so much more than what they are forcing us to accept.”

I’ll never forget when a reader-turned-friend told me I was much less confident and together than I seemed online. She assured me this was a value-neutral statement. It made her feel better, more human. Confidence is not something I intentionally project online—I may even express my fallibility more than the average person—but it’s endemic to the format. Captions, tweets, and essays transmit a sense of finality that normal speech just doesn’t. Static words and images and soundbites can never capture the ineffable quality of someone’s physical presence. To that end, I think our assessments of people online would differ far more to our assessments of them in real life than we might expect. This isn’t to say the internet can’t be exceptionally useful in the human project, only to say it’s not very good at doing what most of us are asking it to do, or what it purports to.

According to anthropologist Robin Dunbar, humans can comfortably maintain 150 stable relationships (commonly known as Dunbar’s number), and no more. The keyword here is stable. Our relationships online are not only doomed to mimic genuine relationships because of the format, but because they’re too plentiful. We cannot reach mass mutual understanding through digital media in any meaningful way. I think we’d do better to accept social media’s limitations—and harness its more useful aspects—than try to overcome them through brute force, a project that’s mostly made the internet more frustrating and fraudulent. As someone whose work and occasional sense of self has been mediated online, this is an uncomfortable reckoning, but a liberating one. I find that the more known I feel in “real” life, the less need I feel to be digitally known. Which doesn’t necessarily translate to deleting my accounts, but a desire to change my relationship to them. If we accept that Instagram or some form of it will never go away, I wonder how we (I) might engage with it in a way that deemphasizes it as a mediator for humanity itself. Is such a shift even possible?

“America Has a Drinking Problem,” one of the most fascinating pieces on alcohol that I’ve ever read (and will never forget!) by Kate Julian for The Atlantic. (You can’t just read the first half—the second is the surprising part!)

This tweet of a Susan Sontag quote, which made me feel seen/attacked.

1 milk chocolate Toblerone bar, which single-handedly finished this week’s newsletter on my behalf. Never underestimate the power of sugar when you’re trying to write.

“Fake Realness,” an essay on the decline of the gay bar by Adam Morris for the Baffler. It’s actually a review of a book on the topic by Jeremy Atherton Lin, but I loved the essay in its own right. I was drawn in by the headline, and found eerie connections to the topic I wrote about this week: “Butch leather bars, Lin believes, are sites of inauthentic performances of masculinity. But they also fashioned a new mode of masculine encounter, one based on fantasy and wish fulfillment.” Inauthenticity as a tool!

The song “Blue Spring” by Nathan Micay, which will take you right back to the HBO show Industry (if you’re into that). A good choice for late-night Ubers if you have the option to choose the music.

The expression “charm offensive,” which I forgot existed.

“Nostalgia Is a Hell of a Drug,” on Gawker’s imminent return by Charlotte Klein for Vanity Fair. I’ve been closely following the hiring decisions by Leah Finnegan and am soooo curious about what the new Gawker will be like. Hoping similar to The Outline (RIP).

“Baby Baggies” and hi-tops for my twin nieces’ 3rd birthday. Totally overpriced kid’s clothes only an aunt and uncle would be dumb enough to buy:

The fight between Floyd Mayweather and Logan Paul…..a consumption decision I wouldn’t dare defend nor promote.

“Caught in the Study Web,” by Fadeke Adegbuyi for Every, about the fascinating world of “study influencers,” a world I was never exposed to as a 2011 college graduate.

The second season of Killing Eve, in preparation for the third season. Continue to be in awe of Jodie Comer and Sandra Oh’s acting.

The genuinely shocking news of how you pronounce inchoate….

Unfortunately two TikTok songs, which went straight to my Summer 21 playlist:

This bonkers profile of “Twitter power broker” Yashar Ali.

Honestly? Mostly just hours of Zelda Breath of the Wild...

On the podcast this week: Spiraling: An Instagram Story

So excited to bring on my good friend Michelle Uranowitz, who I’ve been meaning to have on the podcast forever. Michelle is an actor/filmmaker/teacher and I brought her on to discuss Instagram with me in depth. We rehash some of the above on a more personal level, I make Michelle spiral when I analyze her Instagram, I spiral about whatever I’m always spiraling about, and together we imagine what it could look like to embrace social media as a fundamentally inauthentic medium. Out Tuesday as always.

Thanks for reading! Hope you have a nice week,

Haley

This month a portion of subscriber proceeds will be redistributed to Transgender Law Center, a trans-led organization grounded in legal expertise focused on community-driven strategies to liberate transgender and gender-noncomforing people.

Give me feedback • Subscribe • Request a free subscription • Ask Dear Baby a question