#64: Learning to lose

Maybe Baby is a free Sunday newsletter. If you love it, consider supporting it financially. For $5/mo, you’ll gain access to my monthly Q&A column, Dear Baby, as well as my weekly podcast. Maybe Baby is reader-supported, hence the lack of ads and sponsors. Thank you!

Good morning!

I had a pretty bad July, but today’s newsletter felt something like an exorcism. This is a content warning that below I mention death, but also life.

Learning to lose

The distance between my apartment in Brooklyn and the Delta terminal in the Newark International Airport is only 17 miles, but around 5 p.m. on a summer weekday, it takes about an hour and a half to traverse. First you snake through central Brooklyn, stopping to let Hasidic families dressed in wool tights and suits cross the street on their way home. Then you cross the Williamsburg Bridge and into Manhattan, into the Chinatown streets filled with vendors and tourists in a sea of colorful visors. Next is the slow creep towards the Holland Tunnel, where you can watch the yuppies walk their dogs through Soho and imagine the bureaucratic fights that have taken place on behalf of the 100,000 cars that pass through there daily, funneling in through a chaotic swirl of on-ramps that leave everyone honking in gridlock. Then it’s Welcome to Jersey City!, another 30 minutes on a sprawling cement highway over the Hackensack River and you’re there: in another chaotic swirl of people hugging over suitcases, cars jamming into each other at the wrong angle, someone blowing a whistle non-stop like recess is over.

Yesterday I made this drive to pick up Avi from Terminal B, Passenger Pick-Up 2. It had been a while since I’d left my apartment, let alone my neighborhood, and the sight of so many worlds in such quick succession, the sun glinting off the high-rises and the rivers, the sweaty shoulders and the sunglasses, made my heart sink in recognition. I knew these vignettes—I could smell them. It’s summer in New York. In my stint of seclusion, I’d almost forgotten. I turned up a pop song. I imagined dancing in a club in a tank top, pulling my hair up into my hands to feel the air on my neck. Back home I’d been wearing old T-shirts and listening to the new Clairo album, 45 minutes of sad, plinky piano, or else a Spotify playlist called “Music for Cats 🐱,” also featuring sad, plinky piano, apparently relaxing to cats (less so to me). In the microclimate of my apartment, the season hadn’t mattered in a while. Ostensibly it was high summer, but time had all but stopped since I found out my cat was dying.

Avi was at the airport because he’d been in Madison, Wisconsin, at one of two weddings we had planned to attend this year—the only two trips on our calendars, actually. Both were postponed from 2020 and both happened to take place in the month of July, when our cat suddenly needed full-time care. The flights and hotels were already booked, so we agreed I would go to the first, and him the second, each of us texting constant updates to the other as if something catastrophic might happen if we didn’t. In June, before Bug collapsed, I’d been considering sandwiching a small trip in-between the weddings, and was faux-concerned—in a giddy, post-pandemic sort of way—at the thought of such a busy month. And then suddenly we were cancelling everything, battening down the hatches of our lives in the name of what sounded like the dumbest excuse in the world: “Our cat is too sick.” Somehow, it was true.

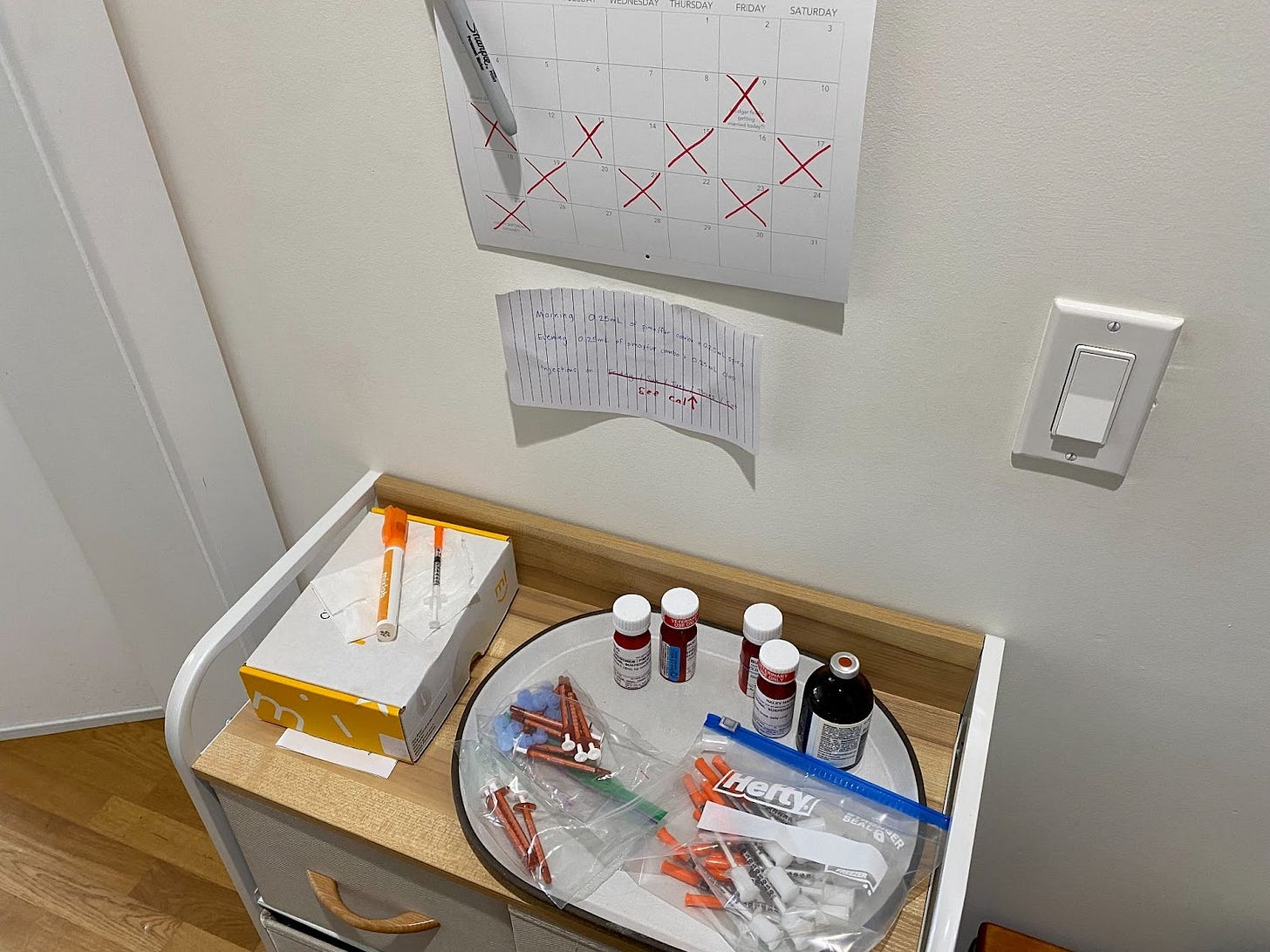

It’s not just that Bug was diagnosed with congestive heart failure and was going to die as a result, it was everything that would happen between those two things. First there was the shock of it—a terminal diagnosis at the tender age of 6—so surprising I lost the breath required to reply to the vet who broke the news. Then the fear, the guilt, the grief. Then the caretaking: the six medications administered throughout the day, the respiratory monitoring, the behavioral observation to check for signs that his lungs had filled back up with fluid. The fact that not even one of them was easy, that each required a kind of panicky day-long vigilance, inspiring its own flavor of anxiety and fear, breaking my heart on a slow drip. Then there was the resulting dissolution of our rapport; the observable loss of who Bug used to be and what we used to have. And finally the fact that optimism meant more of this, which sounded unbearable, or less of this, which meant worse. And so time stalled. Minutes crawling by like my car in the Holland Tunnel. I am not in a club, but I am crying.

In the 1983 film Nostalgia, deemed by some to be one of the greatest films ever made, Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky explores the way time bends and warps according to our attention. In the final scene of the film, a man attempts to cross an empty pool with a lit candle, starting over whenever the wind blows it out. The scene takes nearly nine minutes and is shot in a single take in total silence, except for the man’s gravelly footsteps. The effect is surreal, somehow gripping in its simplicity. I learned about it in a video essay by Evan Puschak called “Time, Tarkovsky, and the Pandemic,” in which Puschak notes that, as you cross the four-minute mark of the scene, “you become aware of the odd encounter you’re having with time itself. You can feel the texture of it, its presence—as if time were not only a concept, but a substance, stretching out in front of you, expanding and contracting with every breath. It’s beyond interest, beyond boredom. Tarkovsky induces a kind of trance.”

Last week, I looked up when Bug first collapsed—it was June 27th—and was so surprised I had to double-check my math. How had it only been three weeks, now four? How was that possible when it had felt like six months? “Scientists imagine the internal clock as a counting pacemaker,” Puschak explains. “The more pulses you count, the longer a given duration seems.” I thought of the way my days have been passing—watching the clock for when to administer Bug’s next dose, literally counting his breaths. “The key variable here is attention,” Puschak says. “The more attention we give to time, the slower it feels.” Imagine freezing in the night when you hear an ominous sound. Now stretch that out for so long you can no longer remember a time before you heard it.

He’s just a cat, is what I tell myself when things feel particularly dark. It never feels particularly true.

How can I describe what it’s like for your every thought and decision to be governed by a terminally-ill cat? I suppose it’s a little like trying to keep a candle lit while walking slowly across an empty, windblown pool. Certainly it requires similar levels of patience, as each environmental shift fills my body with stress-induced cortisol. It’s definitely a form of quiet desperation, albeit one punctuated by moments of joy and relief. There’s even some humor to it, as I find myself invested wholeheartedly in a cause others might find silly: avoiding eye contact with my cat like he’s my childhood crush so as not to scare him away; “playing it cool” in hopes that he’ll come out from under the couch; staying up until 2 a.m. to give him his medicine on his terms, although of course that’s not really possible. I jump at subtle sounds (did he faint?), I gasp when his paw slips on the hardwood floor (is he about to collapse?). If I appear focused on anything else, I’m probably faking it. Is it material, to this metaphor, that when the man finally reaches the other end of the pool, he dies?

Maybe all this would be easier if I were less obsessed with Bug. If I hadn’t adopted him at 10 weeks old, moved across the country with him, spent every day of his life asking him how he was doing and if he was happy (to no avail), kissing him so much more than he cared to be kissed. What if Avi and I hadn’t spent the entire pandemic saying “look” every time Bug moved a paw, or fell asleep, or looked like he always looked, but in a way that hit different this time? We’re not just in love with this stupid little flat-faced cat, he’s the texture of our lives. The thing we look for when we get home, wake up, go to bed, get bored, move rooms, go pee, need love, want to love. We’re self-conscious of how hard we’ve taken his diagnosis. How difficult it’s been to watch him grow afraid of us. How many times we’ve cried because he didn’t trust us to care for him, or how sometimes we cry even when he does trust us, because for some reason that feels sad, too.

I know there are so many worse experiences than witnessing the death of a pet. I know I’ll be okay, and that I’ll still feel grateful in a broader sense. But it’s harder than I thought it would be, or at least more complicated. If only he could tell us why he’s hiding (is he sick? sleepy? dying?), or if he doesn’t like the taste of his medicine (would he prefer it fish-flavored?), or if he understands what’s going on—that we love him, that what we’re doing is “helping him wind down his life,” as my therapist put it. But is that what we’re doing, really? If Bug lives for another year, which seems unlikely but not impossible, should we be thinking of this whole process in such grim terms? How do I enjoy him and also mourn him at the same time? Accept his death and also stave it off? What do I do with the fact that he’s been sweeter to me lately, sitting next to me, sniffing my forehead? Should I be happy about that or should I cry about it? If only he hadn’t collapsed again, been re-hospitalized only 10 days after the first time—maybe then I could believe he’d beat the odds.

Strangely, I happened to be reading This Life by Martin Hägglund when all this started. Hägglund, a philosopher, believes life is meaningful only because it ends, and any religion or belief system focused on eternity misunderstands true spiritual freedom. If life went on forever, he argues, we wouldn’t care nearly as much about what happened to us, each other, or the planet. He calls this “secular faith,” i.e. faith that is worldly or temporal, rooted in what we do and how we do it in the time that we have here. “Secular faith is the form of faith that we all sustain in caring for someone or something that is vulnerable to loss,” he says. Finitude, then, is a prerequisite for care. After we found out about Bug, I had to swap the book out for a novel I’d already read (crisis management), but Hägglund’s ideas have been floating around in my head for the last month anyway, reminding me that Bug’s death isn’t opposed to my love for him, but connected to it. A facet of the love itself.

Something has shifted in the last week. I wouldn’t exactly call it a rhythm, but our obsessive note-taking about what works and what doesn’t is cohering into something we understand, bringing back some version of Bug we recognize. Often it involves ignoring him like he’s a celebrity so he doesn’t feel the need to hide so much, or pretending we don’t know exactly where he is at all times the way Jason Bourne pretends he doesn’t know all the exits in a given room. We’ve learned he can sense our anxiety—not just our hands shaking as we hold the needle or syringe, but our body language an hour before it’s time. So we’ve started playing music in the apartment again, which seems to draw him out. We dance to shake off our nerves and our sadness so he doesn’t catch onto our grief. Sometimes we laugh at the grand performance we’re putting on for him. Sometimes it stops feeling like a performance.

The vets say we are not prolonging his life unnecessarily, and haven’t once suggested we end it. This is just part of the process, they said—the incubation period before his heart, already taxed and oversized, can no longer do its job. It’s all a little devastating, but if you think about it, life is just one big incubation period before our hearts give out, asking us, impossibly, to live fully in the face of oblivion. Maybe even to live fully because of it. “Learn to lose as if your life depended on it,” John Murillo once wrote in a poem. “Learn that your life depends on it.”

Bug’s comfortable, the vets say, breathing. Maybe better than he has in a while.

“The Unknowability of Other People’s Pain,” a moving essay by Maura Kelly for The New York Times about the blurry bounds of endurance.

The show Hacks (the entire season), which I didn’t expect to love as much as I did. Jean Smart is heaven.

“The Climate Crisis Is Worse Than You Can Imagine. Here’s What Happens If You Try,” an amazing and immersive piece of journalism, grounded in a story about a marriage, by Elizabeth Weil for Propublica.

The revived Gawker, which feels so delightfully old-school it feels new again.

This TikTok of a woman telling her coworkers she loved them and filming their reactions, which I’m sharing not because it’s particularly funny or interesting, but because it made me miss having coworkers on such a visceral level that I started rethinking my entire career.

Some quality time with my large adult godson Bryce, whose size is hard to capture but perfect to experience.

“Hundreds of Ways to Get S#!+ Done—and We Still Don’t,” by Clive Thompson for WIRED, a referendum on to-do lists—why we love them, why they punish us, why they are ultimately about death.

“The Great American Cool,” by Safy-Hallan Farah for Vox, about the shifting relevance of what’s “cool” when everything can be bought for cheap, and everyone is buying.

The new, aforementioned Clairo album, which, honestly? I don’t even like.

More cookies (still Smitten Kitchen):

This profile of Jason Sudeikis by Zach Baron for GQ, which I randomly loved, particularly this thing Sudeikis said: “[C]onfidence is a funny thing. You have to somehow believe that the worst outcome simply won't happen. Sometimes you have to do that while knowing for a fact that the worst outcome is happening, all the time.”

Space Jam 2, quite possibly the worst movie ever made.

Chaotically, a Luna bar.

This line on page 219 in The Art of Fielding: “Affenlight realized in what was as close to an epiphanic flash as he’d ever dare to come that there were many ways of living that had never been named or tried.”

That’s it for this week. Hope your Sunday is as soft and structure-less as Bug’s waterbed-like torso.

Haley

This month a portion of subscriber proceeds will be redistributed to National Bail Out, a collective of abolitionist organizers, lawyers, and activists focused on ending pre-trial detention and mass incarceration through community-based advocacy.

Give me feedback • Subscribe • Request a free subscription • Ask Dear Baby a question