#91: The truth parabola

Good morning!

Just a stream-of-consciousness this week, from my brain to yours.

Last Tuesday I started working in an office again. It’s an old, sunny Lower East Side loft with huge windows and leafy plants and pretty girls making jewelry in the back. Sometimes the only sounds in the whole place are of the creaky wood floor and the girls’ fingers poking through plastic containers of beads. This turns out to be my ideal work environment. It’s strange to be back in an office after nearly two years of working from my couch. On my first day I left to get a snack and spent so long walking around the neighborhood that I started to worry someone might tell my boss I was slacking off. Then I remembered I don’t have a boss, and that the concern was just some leftover muscle memory from the last time I worked somewhere that wasn’t my living room. It was a nice moment, actually—realizing I didn’t have to rush back. It reminded me of when it dawned on me in college that I could go to bed whenever I wanted.

Last week was foreboding for many reasons, but I spent most of it thinking I might have to put my cat down, so when I didn’t, things lightened up for me considerably. It’s strange how life goes on when other people are in crisis and you’re doing okay. I know there are people on social media who seem to think you should stop everything you’re doing when something bad is happening somewhere, but then of course we’d never do anything at all. Since the war started in Ukraine, I’ve been seeing calls on social media to “use your platform” and “not be silent.” I’ve been considering these phrases and what they mean. Why they arrive when they do. Obviously they’ve become shorthand for “post political content,” but actually the phrases are fairly vague. Essentially they are calls to open your mouth, to speak. They don’t specify what you should say or whom you should say it to. The reason you should post on Instagram is implied—justice is apparently at stake—but there is no shared understanding of what justice means or entails, or whether the popular interpretation of it at any given moment is salient, accurate, or moral.

I’ve been stuck on the term “platform” and its origins: a person standing on a raised surface, maybe, their face visible and voice audible to the people below them. Then I imagine a town square filled with platforms, everyone scrambling onto them and yelling at each other in a hurry, even the people who have no idea what they’re talking about. Who is left on the ground listening? What are they hearing? My friend recently reminded me of this Kurt Vonnegut quote: “During the Vietnam War, every respectable artist in this country was against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.” Doesn’t comfort me in the least.

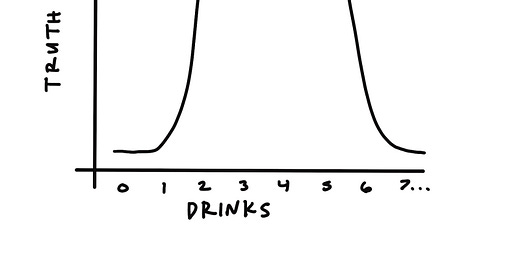

Sometimes I can’t tell what’s more depressing: Having faith in social media to effect change or having no faith in it. On the podcast last week, Danny and I were talking about what we called the “drinks-truth parabola.” That is, the idea that when you’re sober you’re likely to lie, and after a few drinks you’re less likely to lie, and after more than a few drinks, you’re likely to lie again. Something like this:

If it’s true that we’re more likely to lie when inhibited and/or completely out of touch with reality, it would make sense that people are at their most deceptive on social media, where self-consciousness and madness thrive in equal measure. Most people are reluctant to show all their cards when they have an audience. It’s like the difference between an insult someone says to your face versus behind your back: You’re more likely to believe what someone didn’t want you to hear. This reminds me of something Elif Batuman said on a Longform podcast about how fiction is sometimes the most emotionally truthful—so truthful the writers don’t even want to claim it as true, because it would be too revealing. Which makes me think: If denying something is true can be an indication of how true it actually is, what does it mean to insist something is true, like that you’re a good person, say, or that you care about strangers who are suffering? Batuman is obsessed (or was obsessed, in the interview) with the distinction between fiction and nonfiction, and the idea that novels could be truer than memoirs. I like this thought: liars drawn to memoir, truth-tellers to fiction. It reminds me of a running joke online that it’s always the meanest people who post about the importance of kindness.

I know everyone’s been talking about the vibe shift and the discourse already feels passé, but everything I read this week seemed to reinforce its relevance. Joseph Bernstein’s reporting on the art scene of the anti-woke left, all the essays in The Drift’s series on what to do about the depressing state of feminism, Jason Okundaye’s Gawker piece about the narcissism of a certain type of queer activist influencer (which I think applies to many types of activist influencers), Mike Crumpler’s acerbic review of the new Dimes Square play. Each is grappling in its own way with what comes after the culture wars. There’s a tangible impatience to this kind of coverage; people are tired of being quiet and staying out of trouble. No one seems to think this ideological gridlock can last. I loved the kicker of Alex Vudukul’s New York Times piece about The Drift: The writer Sophie Haigney explains that after she published an essay about the cynical banality of children’s books by politicians, a bunch of people thanked her for finally saying what they’d been thinking for so long, and her reply was: “‘Well, then why didn’t you say something?’” If I had to pin the vibe shift on a particular attitude, it’d have to be that one.

Yesterday, a man named Wes cut about a foot of hair off my head—everything that had grown since the pandemic started, plus a little more. When I left the salon, I wasn’t sure if my hair looked “better,” necessarily, but I was relieved it looked different. Sometimes the cause (desire for change) is more important than the effect (outcome of change). Last week someone called into my and Danny’s advice show and explained that she had asked a guy she was dating to open up to her and he’d dumped her, and then she asked for a raise at work and they’d said no. She felt pathetic, she said. She pointed out the popular self-empowerment narrative around “asking for what you deserve,” and said she felt the opposite of empowered. After a diatribe about how the internet has over-simplified and over-mechanized life, we told her she should be proud of herself. In her case, the cause (the bravery to ask for what she wanted) was more important than the effect (whether she got what she wanted). As a culture we’re too focused on effects, like success, and not focused enough on causes, like gumption, even when it fails.

This morning I gave Bug a haircut in my kitchen sink. The aim of the cut was to minimize the amount of hair that gets wet when he drinks water, which leads to infections around his whiskers. By the end he looked like a cartoon character that got in a fight with a pair of scissors: his front legs unevenly shorn, his neck completely shaved, his cheeks rounded out like a cherub, and his back long and fluffy save for a patch where we deliver his shots, which I mowed down like a little putting green. I’ve given Bug more baths and medical haircuts in the last six months than in his entire life prior. Sometimes I wonder if it will be sad or funny to remember him looking like this at the end of his life. It is a little pathetic, visually, but also kind of sweet and natural to prioritize his comfort in such a physically arresting (insane) way. Today in particular he seems to have a new lease on life, post-cut, post-vet, and I guess he really does.

It’s funny, I’ve had a few moments where I looked in the mirror and was startled by my own haircut, too. Occasionally I think it looks objectively worse, and for reasons I can’t quite explain that sends a trace of thrill through me. It can be more interesting to dislike a choice than to ponder one you never make. It’s avant-garde! I mostly like my haircut in the end, but that’s not really the point. Sometimes the shift is more important than the vibe, so to speak.

Haley

p.s. To read last week’s 15 things and listen to last week’s advice show, subscribe here.