Hi everyone,

It’s taken me a while to figure out how to keep my weekly commitment to Maybe Baby when I feel there are so many more important voices to hear from right now. Then again, that will always be true, and when I consider the stated purpose of Maybe Baby—“to explore complicated emotions”—along with my recent addendum to it, “to speak more openly about politics, social media, and the strange intersection of the two,” it would be absurd to conclude there’s nothing I could say right now, to all of you. Especially when I’ve been having so many rich conversations in private.

In my prior newsletters, I think I’ve stated my politics pretty clearly, so when I explore some of my thinking in regards to the current tenor of social media below, I hope it doesn’t come across as anything but a good faith attempt to work out what I’m perceiving as a knot in the muscle of the moment. I also want to clarify that I’m in an admittedly “progressive” bubble, so when I refer to the online discourse, I’m really only referring to a slice of it. The last thing I’ll say is all of these thoughts are in-process, and I’m always open to other perspectives, so feel free to share yours in the comments.

Emotional Paralysis, and Then What?

A couple weeks ago I got a crick in my neck. I’m not sure if it was from lifting something wrong or the way I was sleeping, but suddenly my head was frozen in one position. If I tried to look left or right, up or down, a sharp pain shot through my upper back and gave me a headache. Whatever the physical catalyst, I knew the mental one. I had a crick for the first few weeks of quarantine, too, when I was racked with anxiety and lacking the right precedent to deal with it. When I moved to New York in 2016 and was terrified that I’d fuck up my chance to be a writer, my lower back seized up so badly I couldn’t walk or sit comfortably for weeks. So it didn’t really surprise me that my neck froze just as a new level of rage and conflict gripped the internet in early June. When outward expression fails me, I express myself physically—in the tightness of my neck, hips, jaw, in crumpling up the square inch of skin between my eyebrows like it’s a shitty first draft.

Today is the first day I can look side to side without involuntarily wincing, although the pain is still there, threatening to return if I don’t deal with the underlying cause of the emotional paralysis. Which, I want to clarify, isn’t a big deal in the slightest, nor is it in response to this country’s tradition of state-sanctioned violence, or the unrelenting presence of American imperialism, or the brutal conditions of late-stage capitalism—about those I feel a clear-eyed and confident abhorrence. It’s not in response to the reckoning happening in [largely] women’s media either, which is calling for accountability for past transgressions, equal pay and treatment, and more racially diverse leadership teams—that I agree with. The tension is a response, I think, to how these causes are being metabolized on social media, the digital town square where communication famously and consistently fails us. It’s always been frustrating to watch people misunderstand each other (then hate each other as a result), and it’s even more so on a platform where self-promotion is the founding principle, during a pandemic when life has never felt more precarious and humans have never felt more alienated from one another.

Of course, in many ways social media is thriving. The broad dissemination of funds, petitions, and crucial information; the collective efforts to lift up Black voices and organizers; the pop-up accounts like @justiceforgeorgenyc that are gathering info about protests; the viral educational slideshows that make complex problems easier to understand; the coalescing of like-minded people around specific ideas, like abolition—all these have highlighted the ways social media is a powerful revolutionary tool. It’s part of the reason I can’t stay away. I’m in awe of the people making the most of it right now.

But as every Instagram think piece has covered in the last decade, social media isn’t always used in good faith. And just because I agree with the goals of this movement doesn’t mean I agree with every accusation or opinion or demand offered under its guise, and when those become hot spots for circular and hostile debate, mixing genuine activism with posturing and white guilt and pettiness, I fear that “real progress” is slipping away from us, or that a would-be collective is being cannibalized.

When Altruism and Self-Promotion Mix

One of my biggest mental roadblocks with online discourse right now has been my desire for it to be productive rather than simply punitive. I’ve been trying to remind myself that righteous anger is a powerful emotion, and sometimes ire needs to be expressed and acknowledged fully before resolutions or “productivity” are even considered. Through that lens it makes sense that white people’s apologies and attempts to absolve themselves via internet caption aren’t going over well right now, even if they’re painstakingly worded or offered with good intentions. After all, there are valid reasons to be skeptical. So if we’re calling this moment a reckoning—defined as “the process of calculating or estimating something”—maybe it isn’t so much about resolving problems as it is revealing them on every level. We can’t dismantle something if we don’t all understand exactly how it works.

Which is to say, even if we have plenty of similarities across racial lines that are worthy of mobilizing us as a collective (late capitalism serves almost no one but the 1%), perhaps we can’t effectively coalesce until we fully contextualize and acknowledge our differences. And maybe that process is messy because that’s the human condition, and maybe it’s especially messy because social media presents barriers to communication even as it offers unprecedented opportunity. Acknowledging one’s role in systemic oppression, for instance, can be an ego-destroying effort, which means it will probably always ring a little hollow on social media, which for many of us is the very mechanism through which we prop up our egos. This reminds me of Marshall McLuhan’s theory that “the medium is the message”—that is, how a story is told shapes the story itself. Social media then, as a conduit for self-promotion, will always be a tricky format for altruism. Intentions will always be cast in a shadow of duplicity.

To that end, there is a certain quality to this online reckoning that feels important and different from past ones. There is zero patience for anything performative, which speaks to the concern I raised a few weeks ago about how we square the hard work of allyship and systemic change with the ease of posting on Instagram. I appreciate the extent to which this moment is highlighting the emptiness of lip service when it’s not backed up by genuine action. It’s hard to imagine us ever going back now, which makes me hopeful we may see some real change. And it’s likely we wouldn’t have seen this shift without some missteps and hurt feelings, which underlines why my fear of cannibalization may be short-sighted.

At the same time, when this approach is aimed at individuals, and nothing seems to be enough including full self-flagellation and admission of evils that are likely oversimplified because explaining is deemed defensive, the long-term purpose is harder for me to parse. I agree that impact is always more important than intention, especially when it comes to laws and policies, but I don’t think it’s completely irrelevant where interpersonal dynamics are concerned. So when the pile-on starts to feel purely punitive, co-opted by people who appear to be more concerned with inflicting social exile than progress, the effort feels at odds with the broader movement, which actually seeks to move away from punitive measures to change behavior. It also doesn’t feel fair to the people who are doing call-outs in good faith and aren’t as interested in tearing an individual apart. Online finger-pointing seems most politically useful when it’s part of a broader effort to contextualize and dismantle systemic injustice. Otherwise it feels reminiscent of a neoliberal paradigm whereby individual choices are given more attention than the structural constraints that lead to them.

I’ve questioned whether I feel this way because I’m white, and am therefore naturally empathizing with those being called out because we share a demographic criterion, and that’s definitely possible (although there are plenty of white people I have not empathized with over the past years, many of whom have inspired my own ire and whom I’ve tried to hold accountable myself). But there are strains of feminism that inspire similar frustrations for me. Even as someone who’s experienced harassment and sexism throughout my life, the proclamations that “men are trash,” or that “no men are to be trusted” never quite resonated with me as a political gesture. It was that flavor of simplification that sent me to the left of the democratic party a couple years back in search of a more fluid, idea-based framework—the rigidity of identity politics just wasn’t clicking for me when applied in a vacuum. It’s the same reason I was frustrated by people discounting Bernie Sanders as “just another old white dude” during the early primaries, considering his policies were more progressive and intersectional than any other person’s on the democratic ballot. In my view, this is where identity politics falls short.

Reframing the Problem

The more I talk about all this, the more I want to make something clear: I have zero interest in lodging a defense against internet call-outs. My compassion is focused squarely on the Black and trans communities, the working class, the homeless, the incarcerated, and every other population and combination therein whose lives and wellbeing are simply not cherished the way they should be. It goes without saying that their suffering is unimaginably greater than those facing internet cancellation. I only focus on the above semantics because I want this moment to radicalize (rather than frustrate) as many people as possible. I truly believe it’s the only way we can dismantle the predatory ethos inherent to this country and the few intent on protecting it. So when I notice that the circular loop of shitty apologies and outraged comment threads and righteous one-upmanship I’m seeing online seems more concerned with establishing a moral hierarchy among people who feasibly want the same thing than organizing us, I can’t help but analyze, until my stupid neck is frozen in place, where shit went wrong.

But during my more lucid moments, I have to admit my rumination isn’t getting me very far (or worse, deludes me into thinking that pointing out logical fallacies in my head is doing literally anything for the movement). So today I’m trying to accept this messiness and discomfort as part of the process, like the pressure you apply to a muscle before it becomes flexible, or the micro-tears it endures before it becomes stronger. Maybe both. Progress never comes easily, and history has proven it’s never as linear as monomyths would have us believe. Nor is it always fair. In that sense I think it’s probably presumptuous and naive of me to wish it weren’t so chaotic, or hope it could be more nuanced, or wonder if there wasn’t a more compassionate way to invite people to join the revolution. After all, activists have been doing this work for decades, before I was even alive let alone engaging with their ideas, and there is no universal resistance strategy. I’m just glad it’s happening.

I’ve always been addicted to emotional comfort—whether I’m trying to avoid conflict or delusionally believing I can avoid mistakes if I just try hard enough—and I think this has often been a driving force in my writing: to soothe myself and others into evolving. And yet, the crushing realization that that’s just not how learning works has been a guiding force in my life, too. So right now I’m pushing myself to accept the stumbling blocks inherent to laying it all the fuck out. And trying to remember that when I’m marching at a protest or listening to a rally speech, talking to my neighbors or volunteering in my neighborhood, reading about our untold history or doing literally anything in the physical world, my purpose becomes a lot more clear-cut: to listen to, show up, and care for the people around me, then take aim at the policies and systems that perpetuate inequality. Everything else is probably just ego.

How are you feeling about all of this? If there’s something or someone helping you feel clear and energized regarding the road ahead, I’d love for you to share it in the comments.

*Since I’ve noticed most Maybe Baby subscribers don’t click through to the articles I suggest (lol), I’m going to experiment with putting in drop quotes so you still get something out of it even if you scroll past!

1. Season 4 of High Maintenance, which I think might be the perfect quarantine viewing: short, thoughtfully written, funny and human and sweet. (That said, I think this criticism of the show by Willy Staley is really well-done.)

2. The definition of a “Kafka trap,” whereby the denial of an accusation only makes you seem guilty, i.e. “You’re so defensive.”

3. “The Time I Went On A Lesbian Cruise And It Blew Up My Entire Life” by Shannon Keating, which apparently went viral last year (I missed it). It's a nice long one to get lost in. I found it because it was linked in another of Keating’s pieces, “Am I Writing About My Life, Or Selling Myself Out?” which I also enjoyed. From the cruise piece:

“Per the rules of our loose nonmonogamous agreement, I FaceTimed with my partner about what was happening on the cruise, first telling them about the catamaran girl and then, in so many words, about Lynette. I suspected, even early on, that I was about to break our most important rule of all: Don’t fall in love with anybody else.”

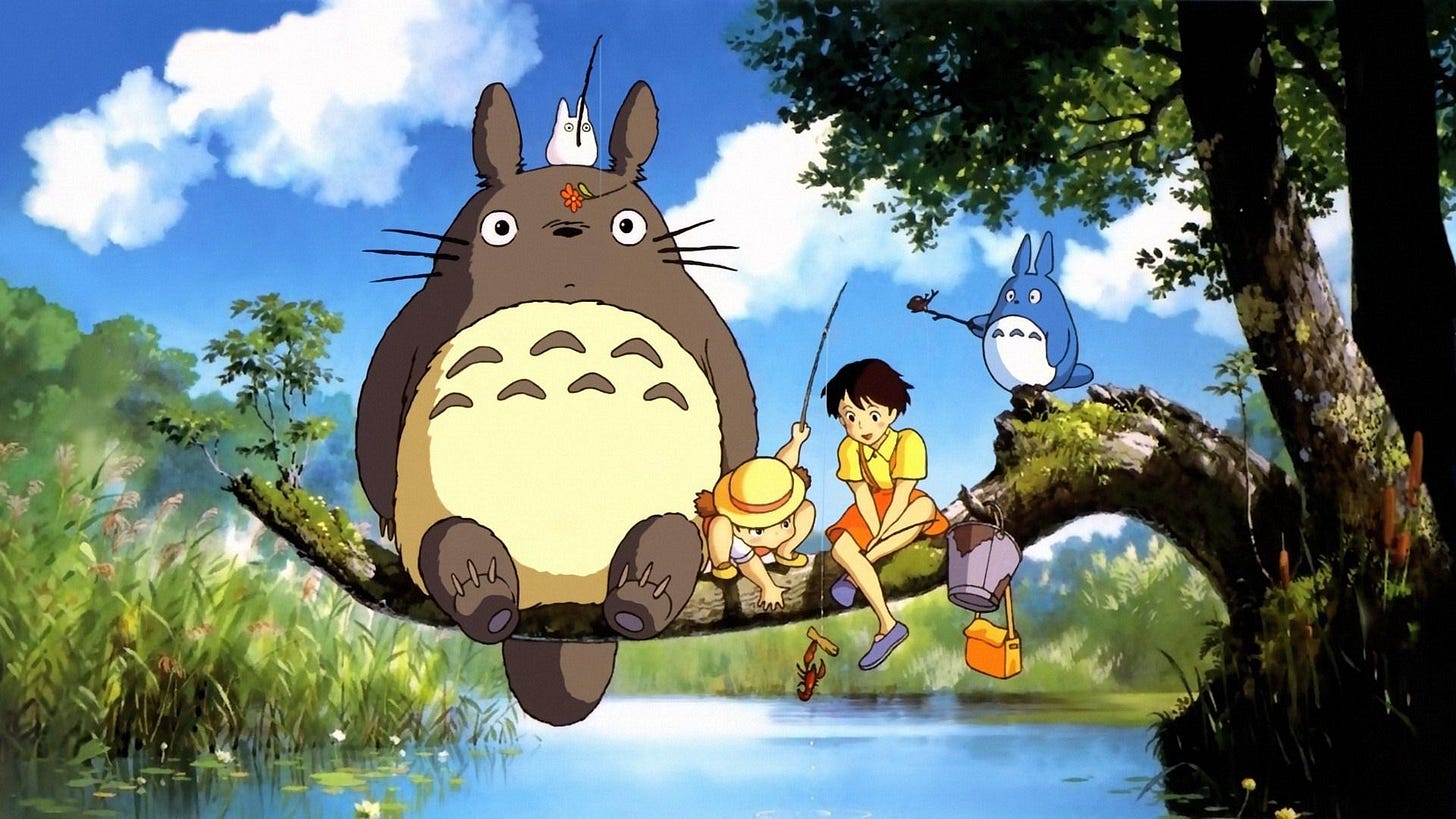

4. Since HBOMax launched, seven Studio Ghibli films directed Hayao Miyazaki, ranked here from favorite to least favorite: My Neighbor Totoro, Ponyo, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Spirited Away, Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke, Castle in the Sky (although I loved them all)

5. The Idiot by Elif Batuman, which proved to be the perfect fictional counterpart to the other book I’m reading, A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn. I always like to balance nonfiction with fiction so my brain gets variety, and where Zinn’s book is sweeping and tragic, Batuman’s was small and cerebral.

6. A piece in The New Republic about why “diversity training” is a lie, referenced in Chapo Trap House’s most recent episode, which critiques the book White Fragility by Robin Di’Angelo. From the article:

“While ruminating on one’s internalized prejudices may require some psychological heavy lifting, there’s little evidence that it helps produce or sustain material change. And though whiteness educators like DiAngelo may employ the radical-sounding language of critical race theory, self-reflection is ultimately a much easier undertaking than working to build a durable political coalition that actually has the leverage to remake society.”

7. This tweet:

...which made me think of something Avi and I made up in 2016: the “Starr-Saint Nicholas” effect, which we defined as the rare occurrence of real life being so on-the-nose you wouldn’t believe it if it were fiction. We named it after a moment on a snowy day near Christmas when we realized we were standing at the festive-sounding intersection of Starr St. and St. Nicholas Ave in Bushwick, which would be too corny to put in a movie. (Another prime example of the Starr-Saint Nicholas effect: that our nightmarish authoritarian leader is named Trump.)

8. The definition of “brownie,” under which the baked good is curiously listed third, after “1. a legendary good-natured elf that performs helpful services at night,” (???) and “2. a member of a program of the Girl Scouts for girls typically in the second and third grades in school.”

9. “Losing the Narrative: The Genre Fiction of the Professional Class,” by James McElroy, which definitely takes some time to get through but which puts words to something I’ve never seen explained before about the way white collar workers are wooed into never changing anything despite being largely unhappy.

“Professionals today would never self-identify as bureaucrats. Product managers at Google might have sleeve tattoos or purple hair. They might describe themselves as ‘creators’ or ‘creatives.’ They might characterize their hobbies as entrepreneurial ‘side hustles.’ But their actual day-in, day-out work involves the coordination of various teams and resources across a large organization based on established administrative procedures. That’s a bureaucrat. The entire professional culture is almost an attempt to invert the connotations and expectations of the word—which is what underlies this class’s tension with storytelling. Conformity is draped in the dead symbols of a prior generation’s counterculture.”

Related:

10. Animal Crossing. I’ve succumbed. No further comment.

11. The definition of an “autological word,” which is a word that possesses the very quality it describes. For example: “word” is a word, “noun” is a noun, the word “short” is short. I learned about this phenomenon when I read somewhere (I forget where, maybe Twitter?) that to accuse someone of “tone policing” could in itself be an example of tone policing. Pretty sure that’s only true in rare cases, but I’ve been thinking of “autological words” ever since. An example of a word that isn’t autological: monosyllabic.

12. Eat Pastry’s vegan chocolate chip cookie dough, eaten by the spoonful, uncooked (obviously).

13. “Joe Biden Represents a Failed White Liberalism” by Malaika Jabali, which does a good job of explaining very plainly where the Democratic party has continually gotten it wrong.

“In contrast to the virulent white nationalism accepted by the Republican party, Democrats have fashioned themselves as the party willing to diversify the beneficiaries of America’s imperialist and capitalist spoils. But this objective has failed black Americans, who are disproportionately loyal to the Democratic party yet suffer most when Democrats make policy with racists and a wealthy minority. Despite the common narrative that the party has had black votes in the bag since the peak of the civil rights era in the mid-1960s, there is a more complicated history with clear implications for the 2020 presidential election.”

14. The new Phoebe Bridgers solo album, Punisher, which I’ve been waiting for since Stranger in the Alps and have thus been listening to on loop.

15. The words “I love New York. Everything is fucked,” said by my brother as we drove over the Manhattan bridge the other night, the city buildings sparkling at us like we were too stupid to know they were no more than an empty gesture.

That’s it for this week. Hold on as best you can. I’ll see you next Sunday.

Haley

P.s. Per my last newsletter’s “pause in programming,” I’ve decided to run my Q&A/advice column, Dear Baby, on the last Sunday of the month (instead of the first). A reminder that you can always drop in questions you’d like answered in the comments. The next round will be next week, June 28th.

"The more I talk about all this, the more I want to make something clear: I have zero interest in lodging a defense against internet call-outs." I gotta be honest: this newsletter definitely read like a defense against internet call-outs, or at least a pretty clear signal that you're verrrry uncomfortable with them. You're sort of framing it as "just asking questions" but I'm not sure the questions are particularly helpful or compassionate right now, at least not for the people who need help and compassion in this moment (Black people). I also think it's good to consider that processing things in public can sometimes be more harmful than you might intend, especially if/when you find yourself saying, "I wonder if I'm just feeling this way because I can identity more with the people doing harm than those being hurt."

That said, if you're going to publicly wring your hands about "call-out culture" and whether or not it's "productive," I think it's incredibly important to at least be really, really clear about who specifically you are talking about (and who you aren't talking about). When you say "when the pile-on starts to feel purely punitive, co-opted by people who appear to be more concerned with inflicting social exile than progress"....who is that about? Are you talking about Tammie Teclemariam, who is going after racists at Bon Appetit? Are you talking about the Man Repeller commentariat? Someone else entirely? And who are the people doing call-outs "in good faith" who you feel these unnamed others are being unfair to? What are some examples of "online finger pointing" that you'd say are setting a good example for others to follow — that you approve of, basically? And how are you, personally, deciding what feels performative vs. good faith? (That's not a loaded question, btw — I think it's good for all of us to try to unpack our strong feelings and opinions about other people's behavior and understand why, exactly, it rubs us the wrong way.)

Basically: without specific examples for readers to go look at and read more about on our own, it's not possible for the reader to consider what you're saying and make up their own mind, to engage in a real discussion about it, or to substantively disagree with you.

As a Black queer woman who seriously side eyes Chapo Trap House, I get the distinct sensation that this newsletter isn't really *for* me (especially after reading the comments) which, of course, is fine. But since you said you're committed to showing up for and listening to the people who are harmed, I thought I'd offer my two cents.

Question for Dear Baby: How do you square your own consumerism (especially around clothing) with your critiques of late capitalism?