Good morning!

I’ve finally written up my birth story, all 4,000ish words of it, for my sweet paying subscribers who supported my maternity leave. I’ve decided to share an excerpt today in lieu of a Sunday newsletter, so if you’re a free subscriber, you’ll find the first half of the story below (then a paywall to read the rest). A big, heartfelt thank you to everyone who subscribed or continued to subscribe during my leave. You helped me so much!

I’m still processing my birth, but I wanted to document it before the details slipped and I started hand-waving it away like a bad dream. In those early weeks, I cried whenever I thought or spoke about it. I wanted so badly to feel differently—to love the way she got here, even if it was difficult. I’m less delicate (and hormonal) about it now, but I still don’t think I’m there yet. She’s so cute and perfect, she should have been born by a ladybug landing on a bunny’s nose. That injustice aside, I don’t think my birth was particularly “bad,” nor do I believe everyone whose birth followed a similar trajectory feels the way I do. So many people have positive birth experiences! It’s all very personal. I find platitudes (or generalizations, like that the hospital is always the problem) a bit insulting to its complexity. Birth is simply wild, and miraculous, and every woman does it alone.

This past week, I recorded a podcast on what’s surprised me about motherhood so far, and although I start with birth (and other physical indignities/triumphs), I feel most strongly about the latter half of the episode, where I talk about how much I truly love it—how fun, enchanting, and expansive it is, where I might have expected drudgery and isolation. After a few people said they’d like to share it with expecting or fence-sitting friends, I lifted the paywall on it. I hope it reaches whoever would like to hear it, and that the intensity of birth specifically never stands in for the whole of what it means to enter motherhood, because it doesn’t for me, not even close.

I used to be terrified of pooping while giving birth. This was before I was pregnant, or even knew I wanted kids, when I was aware of the pooping only as a mythic, nightmarish possibility my friends and I discussed in the same vein as gossip. When the time came to push my own baby out, my legs spread open to a midwife, three nurses, a student, a pediatrician, my doula, and my boyfriend, not only was I unafraid of pooping, I would have had no idea if I had. I was 40 hours into labor, covered in monitoring equipment, and leaking bodily fluids so quickly that the nurse was replacing the pad under my pelvis every few minutes. Shaking in fear and rubbing my own nipples to speed up contractions at my midwife’s instruction, humiliation was conceptually irrelevant. A speck of dust in another room.

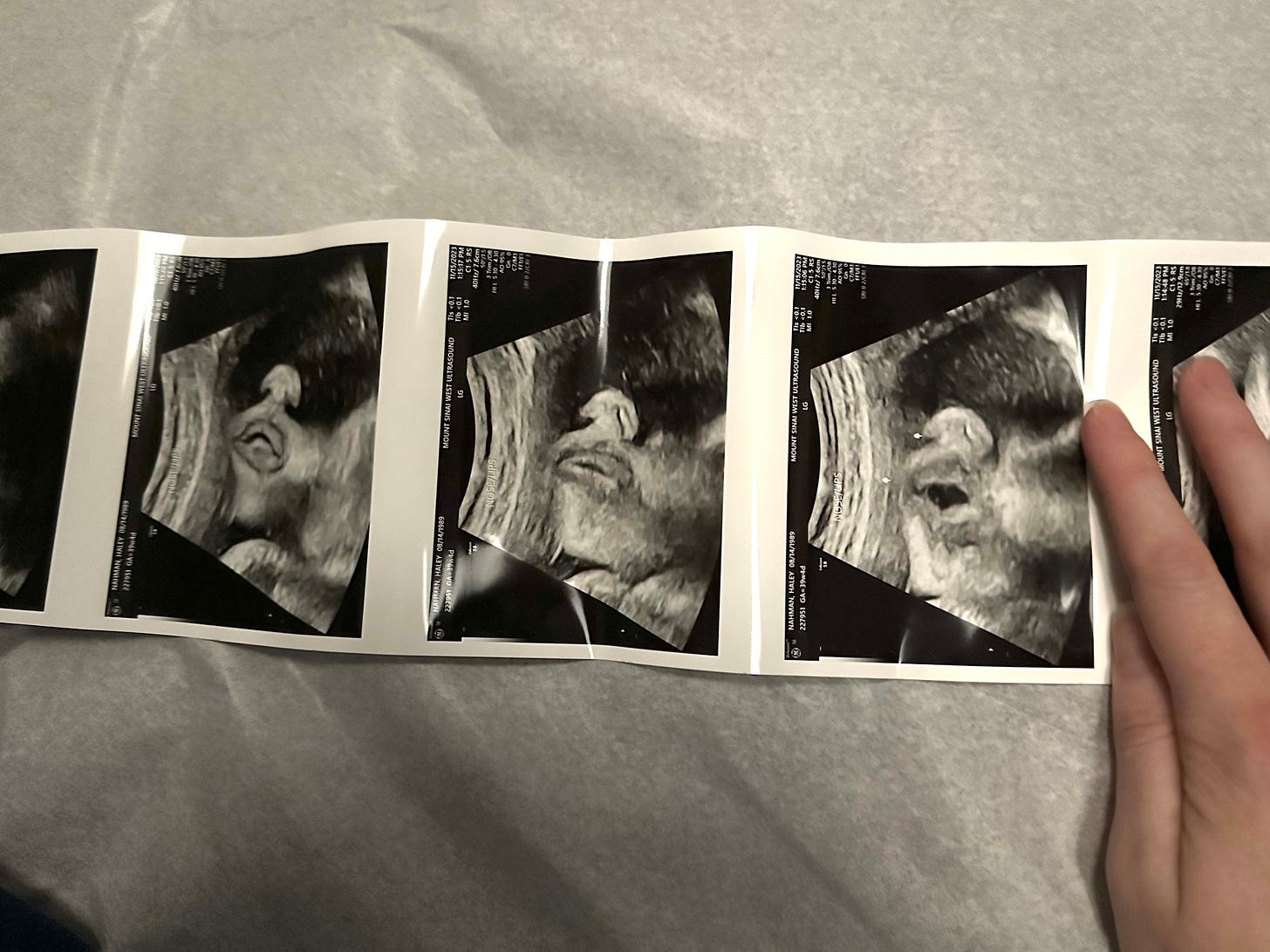

Last November, three days before my due date, Avi and I take the 4 train up to Columbus Circle for my final ultrasound. On the way, I imagine giving birth right there on the dirty floor of the subway car, and quietly wonder if we should have brought our hospital bags. I’ve been having thoughts like this for a couple weeks, but they always feel a little false, like I’m play-acting at someone about to give birth. I’ve hired the doula and taken the classes, for days the baby has felt like she’s going to fall out of my body, but I still can’t imagine it actually happening. In the waiting room, I finally win the unspoken competition of every maternity ward: most pregnant.

This final scan feels like a bonus, superfluous, so we’re shocked when the technician looks concerned and goes to get the doctor. It’s the baby’s stomach, he says, it’s measuring small. He orders a non-stress test, which means monitoring the baby’s heartbeat for 10 minutes while I press a red button every time I feel her move. I’ve never concentrated harder in my life. When a different man comes to talk to me, my heart drops. He says the results look normal, but that I should call my obstetrician. The growth restriction could still be an issue, I might need to get induced.

I make the call on the busy midtown street, hot phone pressed to cold cheek. They ask to call me back. Afraid to get on the train and miss the call, Avi and I walk to Central Park and find a bench to shiver on. He’s annoyed at the patronizing tone of the doctor, who kept referring to the baby’s stomach as her “tummy,” and I’m caught up on whether “stomach” means her literal stomach or her abdomen. Separate gripes to mask the same fear. After 30 minutes, we call back. Doctor is still not available. A kind nurse tells us to go home. Avi takes a photo of me, willing us to one day look back fondly on the moment.

At home on the couch, our doula tells us over speakerphone that fetal measurements scare parents all the time. Usually, it’s nothing. But our doctor finally calls and says she doesn’t want to risk it—I should get induced that weekend. We pick a date and time: Sunday, 6pm. It’s Wednesday, so if I want to go into labor spontaneously, we have three days left to make it happen. The doula helps us hatch a plan for acupuncture and a membrane sweep on Thursday, then a massage and chiropractic visit on Friday. My parents have just landed in New York. They come over to eat pizza and take photos of my bulging abdomen.

The next morning, Avi brings his guitar into bed and plays “Here Comes the Sun,” beckoning her out. We drive to the Yinova Center in Brooklyn Heights for my first appointment. I lay on my side, pricked with needles, while Avi drives circles around me, looking for a parking spot that isn’t there. When I’m done, we meet my parents for lunch down the street, then walk to the water to kill time before my membrane sweep. If you’re unfamiliar, a membrane sweep is “a mechanical technique whereby a clinician inserts one or two fingers into the cervix and, using a continuous circular sweeping motion, detaches the membranes from the lower uterine segment.” Does it hurt? You may ask. The answer to that question—regarding the sweep and everything else in the remainder of this story—is yes.

On the exam table, I take deep breaths. I recall what I’ve practiced over the last few weeks, an ice cube pressed into my palm: Accept the pain. Reframe it as sensation. Relax your body. She sweeps me twice. Within 30 minutes of arriving home, I get my first contraction. A mild seizing of my uterus, like a period cramp. I don’t say anything to Avi or my parents until I feel a few more, in a pattern, and then we start timing them. Twenty-two seconds, five-minute break. Twenty-five seconds, five-minute break. Maybe it’s false labor, but it’s something. I text the doula, my siblings, some friends who insist on play-by-plays, then wander around my living room, my phone filling up with exclamation points.

Before going to bed, I log one more contraction: 1 minute and 31 seconds long, at 10:01pm. I sleep well, only waking a few times to confirm the contractions are still happening, then fall back asleep. By 6am the next morning, Friday, I am wide awake, the contractions stronger but still manageable. It’s the day before my due date. I’m calm but elated. It’s happening! My body is doing this on its own! Days later I’ll recall this moment and my heart will ache a little at the naivety.

Avi and I walk to a cafe a mile away to get breakfast, but the kitchen isn’t open yet, so we get coffees. On the way back, a contraction stops me in my tracks. I grin at him afterward, eyes wide. She’s coming, we feel it. When we get home, I start grabbing onto things when the pain starts, breathing mindfully like they tell you to breathe in yoga class. Michelle texts, asking what the contractions feel like. “A period cramp mixed with a diarrhea cramp but like rounder, in the very pelvic center of my being,” I reply. The doula tells me to go about my day—I’m in early labor, and it might last for a while.

My parents come over around 9:30am to make home-made Chex Mix in bulk—a Thanksgiving family tradition that we decide, inexplicably, ought to occur right now. The next hours unfold as you might expect: Avi, leading me around the house with my hands around his waist, the world’s shortest conga line, which for some reason seems to help; my mom, pouring hot seasoned butter over four aluminum troughs of cereal as my dad stirs. For some reason, presumably a joke, Avatar: The Way of Water is playing on the TV. This lasts for about one and a half hours before I become convinced the sounds of the movie are searing my insides, at which point we turn it off. On the stove, ten pacifiers bounce around a boiling pot of water like rigatoni, sterilizing.

By 11am, the mood has turned. I’m moaning—low, guttural moans, the kind I was too embarrassed to make an hour ago. The contractions are getting strong and I’m afraid of being in the wrong position when they start, because when they do I can no longer move, and then I’m trapped, the heat seizing my abdomen as I try not to clench. My hips are ablaze. I beg Avi to squeeze them, and he tries, but he has a wrist injury that prevents him from applying my ideal pressure: that of an industrial vice. “Her social self is starting to become absent during her contractions,” Avi texts the doula, using the formal language she’s given us. “I’m on my way,” she replies. I’m on all fours in the hot shower, a stream of blood running out of my body and down the drain.

We don’t leave for the hospital for another four hours, which pass like days. I am no longer walking around or leaning on the medicine ball, the pain now beyond alleviation through “the right position.” I’ve taken on a new tack: lying completely still, body lax as if sleeping with my feet in Avi’s lap, channeling all of my energy toward remembering to breathe. Throughout a single contraction I am able to take about four slow, deep breaths, moaning as forcefully as I can throughout the entire exhale, which seems to take a marginal edge off. I’m aware of my parents’ quiet presence, but only vaguely. I want to go to the hospital. Can we go? Is it time? I plead with my doula, as if it were her decision instead of mine. One more shower, she finally says, then we’ll go. I kneel on a towel in the tub, holding Avi’s arms as I expel an angry groan.

Avi steers our Civic through Friday afternoon traffic like he’s landing an airplane in a storm. Hands at 10 and 2 for the first time since his driver’s test. The car is quiet, packed with bags of pajamas and nipple creams and tiny garments. I sit upright, surrounded by pillows, the doula next to me with a reassuring face. The sensation I’m experiencing is so foreign, so intense, that I later have trouble recalling it. In two months, I will accidentally press my finger to a 450-degree pan, and the pain that follows—acute, severe, but lacking sharpness—invites a flash of recognition. In the car, the pain is so extreme I can’t express my reaction to it; it requires too much concentration to endure. Avi taps the gas, pain, taps the break, pain, cobblestones, please no, please, please no. When he says we’re halfway there, as if that’s close, I am too preoccupied to voice my disapproval.

After an hour in the car, we pull up to the gates of heaven, Mount Sinai West. I contract in the lobby, in the elevator, in the hallway, at check-in. I lean against walls, on railings, on desks. There is no room for me in Labor and Delivery, the man at the computer dares to say, it will be a little wait. I want to scream, but I can’t, so I moan. Surrounded by women chatting cheerily as they await their inductions, I climb around on an ugly chair like I’m possessed, the only one in labor, desperate, so desperate, for relief. The sun is going down over the buildings outside the window. I watch them as my insides burn. I forget about the baby at all.