Last Tuesday I woke up in London with a pit in my stomach. It was the last day of my trip and I spent the first hour of it in my friend’s guest bed, scrolling on my phone. When my alarm finally went off, I forced myself up and got dressed. Next to my suitcase, a patch of sunlight warmed the hardwood floor, and a few feet from there, a yoga mat sat rolled against the wall. Noticing these, I plunged into regret, realizing I could have spent the morning stretching lazily in the sun and had instead spent it on TikTok, trying to avoid the feeling in my stomach I had yet to identify. I trudged outside, annoyed with myself.

On my way to the tube, I recorded a voice memo on my phone. I tried to forgive myself for wasting my morning; I tried to locate the source of my swirling stomach. Was it missing Sunny? This was my first vacation without her. Was it wanting to go home? Or not wanting to? Maybe I was nervous that the trip was coming to an end—this trip I’d planned for months as a kind of transformative return to self—and I didn’t have enough to show for it. When I arrived at the station, I pocketed my phone. Ten minutes of audio and no revelations.

I knocked on the front door of my friend Becca’s house at 11am. I was there to meet her newborn baby, a little girl with two dark smudges for eyebrows and a swirl of brown hair that looked like a toupee (perfect distraction). The three of us looped a nearby park then walked to lunch, banking four hours of catching up before I departed with a hug and mapped my way home. When I walked back into the house where I was staying, I found my friend Cam drinking tea in the kitchen in her pajamas. We sank immediately into conversation, and when we sensed we’d never stop without direct intervention, we made an evening plan and got moving. I dressed her in a full outfit of my clothes and we left for Hyde Park, where we wandered through barely discernible statues and dark patches of trees, talking talking talking, stopping only once to watch a bevy of royal swans float around the blackened water.

Eventually I confessed the pit in my stomach—news Cam received with compassion and a little excitement, like I’d handed her a tangle of necklaces. Together we set out to solve it. We considered every angle. I voiced every possible fear just in case it felt true: Was I sad Sunny hadn’t seemed to miss me, even though I’d claimed this came as a huge relief? Was I ashamed that I hadn’t missed her more? Did I worry this made me a remote, disconnected mother, too hard-wired for independence? On and on and on. Eventually we got derailed and wandered away from the topic, but somehow, in spite of the tidal wave of affection I felt for Cam and this walk and our conversation, the pit remained.

Arms linked, we pushed open the heavy door to a cozy French restaurant called Cafe Boheme and settled in at a small table in the back. We translated the menu on our phones and decided to order drinks. The cocktail was a good idea, I thought privately—I hadn’t had one in so long; I needed to loosen up a little. “How are you feeling now?” Cam asked hopefully, sipping hers. “Still there,” I shrugged. She suggested I try a different tack. She told me to pay closer attention to the physical sensation of the pit—invite it in, tell it to grow bigger. I closed my eyes, directing my attention to my stomach, where the pit churned warm and angry. I invited it to flood my whole body, take control. I felt it seep upward into my chest, then into my throat, and finally I burst into tears. The waiter came up just then, shifting the energy, and a moment later I was wiping my eyes in disbelief. I had no idea what had happened, or why I’d cried, or what was wrong. But the pit was gone.

I got back four days ago and have been thinking about this moment a lot. In all my years of writing about my tendency to over-intellectualize my feelings and my desire to stop—in recent memory, on resisting diagnosis, resisting analysis, resisting explanation, resisting comprehension—I’d never considered that it was possible to fully move through and process an emotion without ever identifying what it was. Crying in that restaurant felt like a brief possession, its message almost too on the nose: That day I’d spent 15 straight hours talking with friends about our feelings, from 11am to 2am, and none of it was able to accomplish what my body could in 10 seconds with my eyes closed. A humbling revelation for someone who publishes 2,000 words a week.

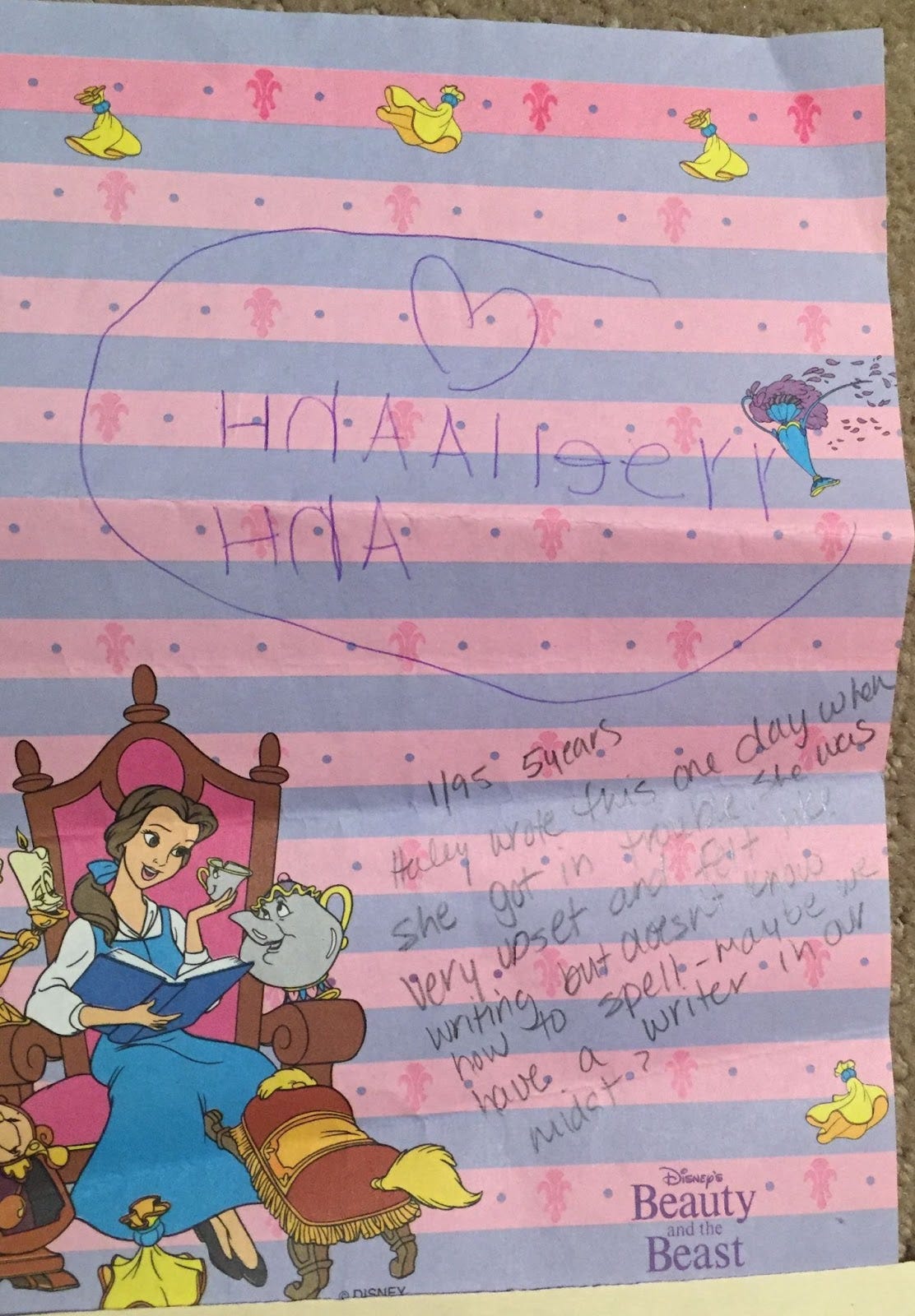

Ironically enough, I keep writing (and writing) about the subject of thoughts versus feelings because it’s the animating tension of my life, and because I assume that if you like my newsletter, you share at least some of my predispositions. Probably the most frequent compliment I’m given as a writer is that my ability to put emotional experiences to words is satisfying (evidently, it satisfies me too). This isn’t just a skill or an occupational hazard, but a lifelong operating principle. Years ago my mom came across an old piece of Beauty and the Beast stationery on which I’d written a string of incomprehensible letters as a kid. Below the message, in her own handwriting, she’d sweetly added, “1/95, 5 years. Haley wrote this one day when she got in trouble. She was very upset and felt like writing but doesn’t know how to spell. Maybe we have a writer in our midst?”

Responding to a feeling with interpretation and analysis can obviously work (don’t unsubscribe!), but that day in London reminded me it can also be a form of avoidance. This is surprising, because technically speaking, I hadn’t avoided anything: I’d reflected on my feelings in private, then paused thinking about them to be present for other people, then been vulnerable, open, and curious about them with a friend. And yet that moment in the restaurant, when I let the feeling spread through my body, it felt like the first time I’d truly faced it. Suddenly the rest of my tinkering with it seemed like a kind of denial, a pushing away. Rather than accepting the pit at face value, as an emotion in its own right, I’d moralized it, then set out to solve it.

The tactic Cam told me to try—turn toward the feeling, invite it to grow bigger—is apparently one used in somatic therapy. In contrast with talk therapy, somatic therapy focuses on the body, especially how it responds to trauma, and presupposes there is always a physical element to emotional healing. It’s very Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score. I won’t write too much about it because I’m not an expert nor a patient in it, but I’ve been intrigued by it ever since another friend told me about her sessions last year, the way her therapist asks her to explain her feelings in terms of bodily sensations. She sent me this handout when I asked her more about it, and I read through it eagerly, side-stepping the parts that sounded pseudo-scientific (as one does). My favorite thing she’s told me is that she’s started to “thank her jaw” when it’s holding tension, as in, thank you, jaw, for trying to protect me in this moment, but I don’t need your help right now.

What I love about all these sentiments, which seem to share a thread with meditative practices, is their lack of judgment. The tight jaw is not wrong, it’s just not needed right now. The pit does not foretell something bad, it just requires my acknowledgment. This reminds me of another tip Cam gave me last week for insomnia (a recent occasional struggle for me), which was to allow my brain to go wherever it wanted to, rather than trying to police my thoughts away from those I’m not “supposed” to have at night, like how strange and impossible sleep is, or how many hours are left before I have to wake up. Funny I’d never considered this while tossing and turning away from “wrong” thoughts: that dodging anxiety was no different than anxiety itself. It’s classic Alan Watts: "Running away from fear is fear, fighting pain is pain, trying to be brave is being scared.” Worrying about a pit is having a pit?

There’s something kind of exciting about observing your mind without trying to control it. My last night in London, with only four hours between bedtime and my alarm for an early flight home, I took my friend’s suggestion and let my mind go where it wanted, with only gentle acknowledgement in the vein of thanking my jaw. I did this for two hours, unfortunately, but I could tell she was onto something. I hadn’t panicked once. On the plane the next day, I attempted this again, casually putting on my eye mask before it felt appropriate, curious to try one more time. I’ve never slept better on a plane in my life.

In Upheavals of Thought, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes that emotions should be understood as “geological upheavals of thought”—eruptions of our subconscious recognition that, in order to flourish, we require things from the world and from other people that are not fully in our control. Emotions, then, are an acknowledgement of our own neediness. Naturally, we don’t handle this well. “Human beings appear to be the only mortal finite beings who wish to transcend their finitude,” she writes. “Thus they are the only emotional beings who wish not to be emotional, who wish to withhold these acknowledgments of neediness and to design for themselves a life in which these acknowledgments have no place.” To think and think and think and never feel—exerting control where we fundamentally weren’t meant to have any.

My eagerness to close my eyes on the airplane and see what happened was an unfamiliar sensation. I’ve spent most of my life trying to figure out how to think well and thoroughly, a process that’s helped me become a careful thinker but also one that’s taught me to receive my untamed internal monologue with skepticism, or just avoid it through distraction. This was a new approach: to be wholly unafraid of my own brain. Curious, accepting, no ulterior motive to correct or control. This was much easier than all my avoidance had suggested it would be. That day in London, it wasn’t the quiet I was running from, but my own judgment. Sitting in the restaurant, eyes closed, I welcomed it all, and then, for once, the chase was over.

My favorite article I read last week was “Anora's American Dream,” by Rayne Fisher-Quann. Last Friday’s 15 things also included recs from my London trip, new glasses I’m considering (lmk), the perfect cocktail ingredient, and more. The rec of the week was your recs of the week, which I love to do from time to time.

Last Wednesday I did another round of Dear Babies, in which I shared a question I received for my advice column that I didn’t know the answer to and posed it to all of you—this one was about a woman who’s trying to decide whether to have a kid with her older boyfriend who is already a (great) father and is having trouble being “all in” on another baby. Amazing responses from you all!

Hope you have a nice Sunday,

Haley

I find it most helpful to treat my emotions like the weather. For our ancestors, extreme weather events were terrifying, and so they created stories about why they were happening (gods being angered, etc), which lead to elaborate rituals to prevent them from happening (sacrifices, etc). Because they wanted to find a way to feel in control. But as we all know, you cannot control the weather. So now when I have those “pit in my stomach” days and I’m looking for a reason, I try to remind myself “I do not need to write a story about why this storm is happening. I just need to take shelter and wait for it to pass.” I also really like your friend’s advice about making it grow bigger. I’ll try to remember to add that to my practice.

Your childhood note says, "Hhaalleeyy"! You probably realized that already. I teach 5 year olds and it is so fun to decode their writing.