A couple of weeks ago, on Tiktok, recording while seemingly naked in bed, Charli XCX admitted she was sad about BRAT nearing the end of its cultural lifespan. “It’s really hard to let go of [it] and let go of this thing that is so inherently me and [has] become my entire life, you know?” she said wistfully. She acknowledged celebrity oversaturation is risky, and that maybe she should heed that, “but I’m also interested in the tension of staying too long. I find that quite fascinating.” You should watch the whole video if you’re interested—she goes into more detail.

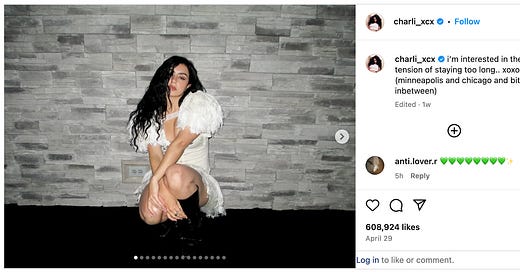

Watching this I felt a flash of judgement—give up the spotlight!—then protectiveness (please rest), then something more curious and admiring of her vulnerability: This is not something most would admit out loud. What does it mean, really, to “stay too long,” and where does the desire come from? At one point she refers to the cultural “ebbs and flows” of celebrity public awareness, and she mostly chalks it up to PR strategy: Don’t show your face for too long or people will turn on you. Subtext: especially if you’re a woman. From that perspective, overstaying your public welcome feels like an interesting provocation (and might explain why she repeated the idea in an Instagram caption two days later like a playful threat). Still, I think the better question regarding fame isn’t whether you’re allowed to “stay too long,” but whether you should.

I’ve written about my own ambivalence regarding the spotlight, but I haven’t always felt the way I do now. There was a time when I believed it could solve a lot of my problems—an emotion I link most tangibly, if you can believe it (so millennial), to the first and only time I’ve seen Taylor Swift live. It was the Santa Clara stop of her 1989 tour, 2015, and my 26th birthday, but emotionally speaking, I could have been 16. I’d been invited by a friend, and was probably excited, but what I remember most about the night was my angsty cynicism by the end—about the jumbotron videos that played between songs of her famous friends saying how amazing she was, and about the god-like figure she cut on stage, a glowing pinpoint of significance surrounded by a dark mass of roaring fans. I was stunned by how beautiful she looked, and how beautiful it looked to be her. It was like a cult! I said to friends afterward, genuinely freaked out. What I didn’t say was that I was also jealous.

I’m not sure what gave me the gall to consider myself in competition with Taylor Swift, but we were (are) the same age and had the same blond bob, so maybe it was out of my hands. Regardless, the odds weren’t looking good for me. Whereas she was a world-famous popstar, I was a confused HR manager, writing furiously on Wordpress about some jeans I bought from Zara. In six months, I’d get a job offer at a fashion website and move to New York, where my ideas about fame would be thrillingly challenged, but at the concert, dancing in the cheap seats, my anonymity felt like a plainly bad draw. I was old enough to know fame was a messy business, but that night, she looked like the happiest person in the world.

Ten years later, I still think of that arena tour and the nauseous mix of revulsion and yearning it produced in me. I was more comfortable with the former than the latter, fancying myself closer to a “critic” of Hollywood than a hopeful. But looking back, my yearning made sense; to be spotlit would suggest (maybe) a public alignment between what I wanted to do and be and what people wanted from me. I longed to be seen and appreciated for who I was, essentially—found, rather than lost—and to perhaps (why not) be deemed exceptional in the process. From a practical distance, achieving public success scanned to me as belonging, which is ironic, because what I’m talking about is actually separation: an elevation of my own standing above the crowd. This must be one of the most common misapprehensions about fame, while somehow also being the most cliché.

After I moved to New York and started garnering some attention for my writing, I finally got a partial view from the pedestal: I gained some “fans,” and sometimes they’d recognize me on the street. For a while, the flush of self-esteem this gave me was so comforting I mistook it for the spiritual alignment I sought. I was finally doing what I was “meant” to do. To be recognized, after all, was a way of being affirmed. If there was a difference, I wasn’t clocking it. Yes, yes, my ego was involved, but that almost felt incidental—a sweet little payout care of the attention economy, nothing so dramatic as a corrupting force. That only applied at the scale of real celebrities, not writers for cult fashion blogs.

This worldview lost its shine in the usual ways. I met some of my heroes and some of them sucked; I attended events that were hollow and demented but looked fun online; I eventually realized the best parts of my life weren’t exclusive whatsoever but run-of-the-mill: a result not of being elevated above my peers (on a stage, say) but thrust among them (in the crowd). In time I came to see these positions as diametrically opposed—not in the sense that one is good and the other bad, but in the sense that they can’t be held at the same time. To be in the crowd is to cede your elevated position and commune with your peers, share experiences and navigate your differences. To be loved and admired by that crowd (or even to be loathed by it) is to be, on some level, alienated from it.

The spotlight offers genuine benefits, obviously. In my case, I earn a living (doing what I love) by virtue of an audience, and it’s true what I thought at 25, that it would mean a lot for my natural predilections to align with my job. I don’t take that for granted (also, it’s just fun). But I’m more aware now of the difference between connecting with a stranger because they know my work (flattering!) and connecting with a stranger because we both just witnessed the same absurd thing, or live on the same block and are admiring the same tree, or both gave birth and feel insane. If you’d told me, before I was ever stopped in the street by a reader, that conversations brought about by shared experiences would be equally satisfying—that actually, the latter could feel more life-affirming, more transcendent—I wouldn’t have believed you. What could be better than feeling so fucking special? The answer, I think, is not feeling so alone.

Charli XCX has tried, to an extent, to break down the barrier between artist and audience, challenging the edict that it’s lonely at the top. She brings so many friends on stage you can barely distinguish her among them. She lowers herself down into the throng, partying with the crowd like they’re all there for the same reason. When she wins three Grammys, she says, “We’ve won 3 grammys!” Still, the barrier remains. Over the last year, Charli has been photographed, observed, and interviewed on a loop. She speaks the language of her fans like she’s one of them, but when she says something funny, people laugh a little too quickly. When she shares an idea online, the yeses multiply across the internet. Given that she’s been previously overlooked for her talents, I’m sure the reception of BRAT has been deeply satisfying (she’s said as much). But the spotlight’s burning hot, and as her time in it wears on, her tone’s grown parodistic, even claustrophobic. Trafficking in attention requires a kind of solipsism: You are the world, so you just keep spinning.

“I kind of want it to go on and on and on because it’s who I am,” she said in her TikTok. I wonder about that. What does it mean to fully self-identify with your artistic output, or marketing concepts, or public reception? What is sacrificed when your primary mode of relating to the world is by way of attention received rather than by attention exchanged? Is human connection truly possible when you hold so much power over other people? Who do you become without it? This, I think, is the real tension of staying too long.

In Fan Fiction, Tavi Gevinson’s narrator explores being at the helm of Rookie during her high school years, when her “friend group was a global community of sweet nerds who revered me.” She describes the meetups full of “tearful teens attending in such good faith that they practically glowed,” after which she would return to her hotel room alone, and cry. Later, she struggles to carry on a friendship with Taylor Swift, unable to cede her role as a fan. Again and again, she tries to meet Taylor on her level but finds herself kneeling beneath her, worshipping. After a weekend at Taylor’s beach house, she posts photos of it to a secret Instagram account. “The posts felt amazing,” her narrator writes. “I beheld them like jewels ... But I could never post like this on my regular account. That would be fan behavior, tacky, uncouth. No one who truly belonged in that weekend would do such a thing.”

There it is again, that ill-fated delusion: to be special is to belong. To be spotlit, and comfortable there, is to finally be home. I want it to go on and on and on because it’s who I am. There’s a rigidity to the dynamic between a public figure and the public, no matter how porous and genuine we believe the figure to be. Which isn’t to say the dynamic is unbreakable or irreversible, just that it nonetheless shapes and shifts behavior, thus interrupting the potential for unmediated connection. This is why trafficking in attention is a dangerous game—full of opportunity, yes, but with risks on the level of the soul. To stay too long, to invest too heavily in your separation from the pack, is to lose touch, I think, with your own humanity.

Many seem to believe fame is fun until it’s the big, bad, alienating kind, but I’d argue the challenges start at the beginning—with any modicum of attention online, say—and scale from there. Finding peace, I think, requires a certain trepidation around your desire to be seen as exceptional. I saw this idea captured perfectly the other day, by the actor Brennan Lee Mulligan in an interview. “It is good for you to be forcibly ejected from the story you are constantly telling yourself about your own life,” he said. He was talking about living in New York—how the population density regularly forces you out of yourself—but he could have been talking about the choice to fade into any crowd. “It’s so good for the soul to be here,” he said, to remember that “you’re very much not the main character—you may be shoulder to shoulder with someone who you’re like, today is really about them.”

My favorite article I read last week was (relevant!) “Critics, Fans, and Subjects (with Tavi Gevinson),” a great conversation between Tavi and Rayne Fisher-Quann on navigating celebrity and taking risks. Last week’s 15 things also included some kids clothing recs, the best Met Gala outfit, an insanely good cookie recipe, and more. The rec of the week was the best iPhone case (which I need badly). Last week’s podcast was about the difference between documenting your life and memorializing it. So much to think about!

Happy mother’s day 💝

Haley

I have a friend who’s spent her whole career working alongside famous people, first as a PA for a-list celebrities, then as a business partner to a-list thinkers. We were talking about the nature of fame once, which you’ve articulated so beautifully here — how lonely it is, how it warps your sense of self and worth — and I asked her if she thought anyone who aspires to the spotlight has a clear inkling of what it entails. She immediately responded, “No. No one who has any understanding of fame would ever want it.”

A few months ago, I got to go back stage at a concert for one of my favorite bands because the friend I was with is a famous comedian. He’s not someone I knew of before our friendship, but I’ve never been anywhere with him publicly where he hasn’t been stopped by fans. I asked him if he thought it’d be weird if I went up to the lead singer and said how much I loved his music. He told me not to do it, because “You can never be friends with someone who’s your fan first.” It made sense, but it also kind of shocked me— I thought about the hundreds of people I’d seen come up to him over the years, so eager for that moment of connection. It was the first time I realized that for him, there was no connection in those interactions — just the isolation of the spotlight.

There’s a book I tried to read once- how should a person be by Sheila heti. The prologue was so good! About fame and attention and self perception that the actual story after it couldn’t hold my attention.

“How should a person be? I sometimes wonder about it, and I can't help answering like this: a celebrity. But for all that I love celebrities, I would never move somewhere that celebrities actually exist. My hope is to live a simple life, in a simple place, where there's only one example of everything.

By a simple life, I mean a life of undying fame that I don't have to participate in. I don't want anything to change, except to be as famous as one can be, but without that changing anything. Everyone would know in their hearts that I am the most famous person alive-but not talk about it too much. And for no one to be too interested in taking my picture, for they'd all carry around in their heads an image of me that was unchanging, startling, and magnetic. No one has to know what I think, for I don't really think anything at all, and no one has to know the details of my life, for there are no good details to know. It is the quality of fame one if after here, without any of its qualities.”