A month ago, my brother asked if Avi and I were free at 7pm the following Friday if he promised to babysit. Intrigued, obviously, we said yes. He sent us a nondescript ticket with an address, and told us nothing else. When we arrived, we were confused to find a store. It was called Art of Play, and it appeared to sell a category of item I refer to (lovingly) as “stuff my dad kept on his desk in the 90s”: twirling magnetic contraptions, trick puzzle boxes, trippy spinning tops that hypnotize onlookers when spun. It kept going: stained-glass kaleidoscopes, a mechanical hand that eternally tapped its fingers, an elaborate moving sculpture made of clock parts that counted time via cascading metal balls (for the humble price of $12,000). I may be overestimating my dad’s desks.

Eventually a man introduced himself to us, asking our names with a pointed familiarity that made us a little nervous. At this point, we’d surmised this was a magic shop and we were going to see some magic, but we weren’t sure where or how or who would perform it. He asked if we wouldn’t mind sitting near the front (what front?) to assist in the show (what show?), to which we said yes, and then glowed at each other like we’d been cast in the high-school musical. When the store was full and the clock struck 7, he addressed us all, gave a charming speech, then led us into a dimly-lit theater we’d have never known was there.

While everyone else was guided toward benches arranged in tidy rows, Avi and I were led to two chairs on either side of a table at the front, alarmingly on display (I urgently tried to fix my hair in the True Mirror by the bathroom, which had little impact). The man then introduced the guest of honor, the famous German sleight-of-hand artist Denis Behr, who towered over everyone so impressively it almost felt like part of his act.

I was instructed by Behr to shuffle a deck of cards, count out 10, then place them in an envelope, which remained untouched in front of me. Next, he asked Avi to count out 10 too, then handed him a sharpie and told him to write his name on the two lowest cards, which he did in big capitals. Soon after—what could he have possibly done in that time?—he asked me to open my envelope, still in the same spot, and inside, of course, but Jesus, how, were two cards with AVI written on them, in the handwriting I know and love. When I found them, I was so stunned, so mystified, I felt physically ill. He boxed up the deck and, later, let us take it home.

I won’t say much else about the act—the man who greeted us, who turned out to be the owner of the shop and theater, advised us to preserve the experience for others, as my brother had done. I’ve already said too much! But throughout the show, I kept thinking about how special it was to spend an entire night reveling in unanswered questions, and how seldom I seek out this feeling in other contexts. At one point, I mistook a pulsing vein in Behr’s arm for a wire tugging on his skin that I wasn’t supposed to see, and for an instant, I despaired. When I realized my mistake, I felt a flood of relief.

I’ve only been to a few other “magic” shows. Most memorably, a performance by the mentalist Ryan Oakes, at my 30th birthday, who crushed, and Derek Delgaudio’s In & Of Itself, which stands out as one of the most remarkable events I’ve been to in New York (we left in tears). Each time, I’ve been surprised to discover my own desperate clinging to naiveté, an emotion I otherwise don’t identify with at all.

People who work in the field of illusions guard their secrets with a kind of existential sincerity, which I find extremely charming. They understand that while some people, in their incredulity, may be desperate to know how things work, it’s in both parties’ best interest that they never find out. Professionally speaking, this refers to the Magician’s Oath (or Code), “a set of principles and guidelines followed by magicians and performers to maintain the secrecy and integrity of their art.” Given it’s mostly an oral or even unspoken tradition, the details of the oath vary, but the broad strokes, laid out on countless informal webpages like this Reddit thread, are:

As a magician, I will not reveal the secret of an illusion to any non-magician, unless that one swears to uphold the oath in turn.

I promise never to perform any illusion for any non-magician without first practicing the effect until I can perform it well enough to maintain the illusion of magic.1

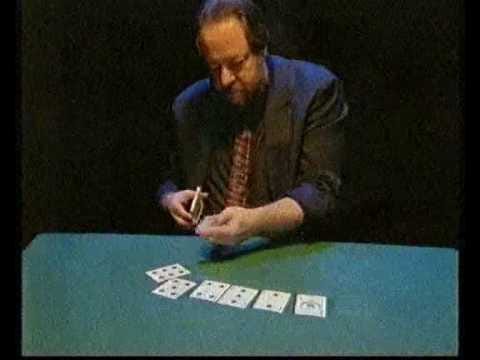

After the Art of Play show, I revisited Mark Singer’s famous 1993 New Yorker profile of Ricky Jay: “Secrets of the Magus.” In an hour-long read that’s a non-stop delight, Singer paints a portrait of one of magic’s most idiosyncratic practitioners and scholars, one who was utterly devoted to protecting the integrity of the magical arts. I first read the profile in 2021, after I shared the below (amazing) video of Ricky Jay doing a card trick and someone recommended it to me. Jay died at the age of 72 in 2018.

Jay was devout, amassing a book collection of “several thousand volumes, plus hundreds of lithographs, playbills, pamphlets, broadsides, and miscellaneous ephemera” on the magical and mysterious. He was obsessed with (and cranky about) “the critical distinction between doing tricks and creating a sense of wonder,” wrote Singer. “One guy in a tuxedo producing doves can be magic, ten guys producing doves is a travesty.” He was also mysterious himself. As his friend, the screenwriter Janus Cercone, put it: “I talk to Ricky three times a day. Other than my husband, he’s my best friend. I think I know him as well as just about anyone does, and I know less about his background and his childhood than about those of anyone else I know.”

Inscrutability wasn’t an unusual quality among his peers. I was struck by this anecdote from one of Jay’s most trusted confidants, Persi Diaconis, also a world-class sleight-of-hand artist, about another magician, Dai Vernon, from whom Diaconis received a magical education, and whom Jay referred to as “the greatest living contributor to the magical art”:

“‘Life with Vernon was a challenge,’ Diaconis says. ‘Vernon would use secrecy as a way of torturing you. When he and I were on the road, he woke up one morning and said, ‘You know, I’ve been thinking about sleight of hand my whole life, and I think I now know how to encapsulate it in one sentence.’ And then, of course, he refused to tell me.’”

Imagine how annoying! This level of commitment to forcing wonder is honestly inspiring. Throughout the profile, Jay was evidently disturbed by the cheapening of magic in contemporary (1993) life by entertainers like David Copperfield, who he saw as more interested in profiting off the art than respecting it. I have no doubt he was appalled by the late 90s/early aughts TV show, Breaking the Magician's Code: Magic's Biggest Secrets Finally Revealed, which aired on Fox and earned its host, the magician Val Valentino, several lawsuits and general disdain from the magic community for selling out. I can only imagine how Jay’s feelings evolved as the internet reached maturity and amateur magicians became incentivized by algorithms to share sought-after knowledge and the general population grew increasingly entitled to answers.

My enchantment at the Denis Behr show a few weeks ago felt amplified in response to what the rest of life has felt like lately. I was fresh off a weekend with my beloved parents, who have taken to ChatGPT as cheerfully as college students, and who were excited to show me just how instantly it could draw conclusions on anything we wondered about over the course of their trip. I guess I was feeling a bit worn out by answers. To be fair to my parents, I’m no less entitled to knowing stuff—I may have misgivings about AI, but I Google things basically all day. We share the same human impulse to search for answers. I’m just not sure we were supposed to get so many of them.

The modern obsession with answer procurement reminds me of what Oliver Burkeman calls the efficiency trap. I read about this idea in his book Four Thousand Weeks, which is a critique of productivity culture and isn’t strictly related to AI or anything like it, but maybe you’ll see the connection too. “Rendering yourself more efficient,” he writes, “either by implementing various productivity techniques or by driving yourself harder—won’t generally result in the feeling of having ‘enough time,’ because, all else being equal, the demands will increase to offset any benefits.” I sense a similar predicament in the context of AI or even simpler search engines. Putting so much stake in the answers—rendering our wonder more efficient or productive, you might say—presupposes that the answers, and not the questions, are the point.

The night before Father’s Day, when my parents were still here, exhausted from the afternoon but determined to fit one more thing into our day, my mom and I decided to make “overnight French toast,” an indulgent recipe that involves (as you might guess) soaking bread overnight. While cutting the French loaf, my mom misread “one-inch slices” as “one-inch cubes,” and proceeded to slice the bread into a bunch of little pieces. Upon realizing her mistake, we decided to improvise the rest of the recipe, knowing the original prescribed method wasn’t going to work. Having no guide but pure delirium and whimsy, my mom and I finished the recipe in hysteric fits, stirring chunks of bread around a pan in a cinnamon-swirled slurry. With wavering faith our tweaks had worked, we rehearsed how we would each blame the other at breakfast the next day.

Something about this experience unlocked a memory for both of us—of staying up all night working on my 5th grade school project about Ireland, so totally lacking in resources we took to hallucinating facts about the country and, infected with laughter, writing them down between gasps for air. The memory stood in contrast to a moment earlier that weekend when, wondering how to cook such and such, one of us had consulted our phones and conjured a thorough and scientifically accurate answer. “Huh!” we all said, then moved on with our lives. Meanwhile, our Frankenstein French toast, apart from one pocket of raw egg experienced by my brother, was transcendent.

What magicians like Ricky Jay offer us is a reminder that it can be infinitely better to live life in the questions, reveling in the absurd and experimental, than to know exactly how everything works or ought to. Beyond that, they teach us that wonder, more than merely a worthwhile human experience, is something that requires active protection—a willingness, even, to feel annoyed or desperate in the face of the unknown. To wonder is a human impulse and a bottomless well of a gift, not a problem to constantly solve.

At one point in Singer’s profile, an accomplished magician named Steve Freeman describes being tricked by Ricky Jay one night at dinner. Earlier in the evening, he’d brought a shirt to Jay, who’d told him to put it on the back of his chair. Later, Jay offered to show him a new trick. “He spread the deck face up and told me to point to a card,” Freeman says. “I did, and then I gathered and shuffled and dealt them face up. There were only 51. I didn’t see my card.” Jay told him to look in the pocket of the shirt, and there it was.

Unable to comprehend how this worked, Freeman being a professional himself, Jay was deeply satisfied. “I felt stupid,” he concluded, “but it was nice to be fooled. That’s not a feeling we get to have very often anymore.”

My favorite article I read last week was “Martyn Stewart, the Man Who Collects the Earth,” by Laura Bannister for Esquire, a lush and moving profile of a sound recordist who has nearly 100,000 recordings of life on Earth. Last Friday’s 15 things also included a haunting (and addicting) novel unlike anything I’ve ever read, a curious physical therapy accessory, a delightful addition to my home-eating experience, and more.

Last week’s Dear Babies was about what to do when the person you love lives in a city you hate (or vice versa). Soooo much amazing advice in the comments of this post! I feel like this thread should become the go-to destination for navigating this issue.

I hope you have a nice Sunday,

Haley

There is also a more detailed “official” version by the International Brotherhood of Magicians. Side note: Why does the magical profession feel pathologically male?

I love the double layer of wonderment in your brother’s quest to get you to experience something with very few prior details, just pure trust- a situation where the bases of your kiddo’s care are covered so there’s no wonder there. All wonder, upon arrival to a secret place could be focused on what magical event might take place. It’s fun to think specifically about how your mind must have been swirling, and hell, let’s add a triple layer of wonder- your brother at your home with his own mind swirling around how you were experiencing. Very sweet to think about. I will be looking for more Just Trust Me moments to give and get in my own life.

I used to work with a girl who was Ricky Jays archivist and librarian and she told me there is a magic library in midtown that only magicians can enter and I’ve never googled it because I like what I’m picturing more than what is likely reality.