Hello.

Last week I didn’t open the front door of my apartment for three days, obliterating rule #4 as if I hadn’t written it myself. In my defense, I was busy with a copywriting gig (rather than depressed), but still, by day four I woke up feeling like a corn husk. Dry, papery, disposable. So I forced myself on a short walk.

As I snapped on a medical mask and stepped outside, I wondered if breathing into my own little muzzle counted as “getting fresh air.” It didn’t feel very fresh. Especially since I’d worn this particular mask several times already, and at a certain point it started to feel like putting a pair of underwear back on after taking a shower, which I hope we can all agree is a cursed experience. The walk was fine. The “park” near my house is now officially closed, so I can no longer do figure-8s around the handball court while I think about the kids who should be occupying it, which is probably for the best.

The masks are everywhere. It’s rare to see anyone in New York anymore without one. The recycled breath and foggy glasses aren’t ideal, but I think the most disconcerting part of the civilian mask experience is not being able to smile at strangers. I didn’t realize this was so important to me—this toothless little facial tick that signals I mean no harm on empty city blocks—but in its absence, I feel like a ghost haunting Brooklyn, disappointing Tyra with my inability to smize through the holes in my ghost-sheet.

Yet there is something kind of nice about this, too. I no longer have to manage my face; I no longer have to engage my toothless little facial ticks to signal I mean no harm. In that way it feels like a pint-sized respite, even if it isn’t ultimately worth it. This is true in its own right, but it’s also a metaphor for quarantine.

Adapting in captivity

Here is something I did not expect: It’s possible to get used to staying in your house all day, not seeing anyone you know, and generally being deprived of physical experiences that aren’t shuffling around your apartment and opening your snack cabinet every 42 minutes. I may not love my life right now, but I am growing used to it, and I’ve been surprised to discover just how restorative that transition can be—to go from shocked to acclimated. Horrified to pacified. Maybe going into self-isolation is like jumping into a cold lake: The initial plunge is the worst, then after a while you’re just numb.

In conversations with friends, I’ve noticed a similar shift towards tolerance. The panic has receded a little, and approaching is a kind of patience. There’s something existentially bolstering—if simultaneously unnerving—in the realization that you’re capable of adjusting to conditions you once found unbearable. A few weeks ago I couldn’t imagine it possible, which was in itself a catalyst for despair. Where else could we spiral but down as our jobs disappeared, the bad news multiplied, and our social lives pruned like fingers in a tepid bath? But I should have remembered our biological imperative to adapt.

The hedonic treadmill: “the observed tendency of humans to quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes.”

The hedonic treadmill is why the promotion only feels good for a week, and the breakup doesn’t hurt forever. The term was coined in 1971 by two psychologists, but the idea’s been around for a long time. "A true saying it is: Desire hath no rest, is infinite in itself, endless, and as one calls it, a perpetual rack, or horse-mill." Saint Augustine said that, and he was born in that year we all know and love: 354 AD. He was coming at the topic from a different vantage point, but the idea is the same: There is no peak at which we’ll be permanently happy, and no dip from which we’ll never recover. Some neurologists believe our brains aren’t even capable of sustaining extreme emotions.

(I once wrote about this concept for Man Repeller in an essay called “Changing My Life Didn’t Change Me as Much as I Thought It Would.”)

The extreme emotion that could simply not be sustained in my brain was one of utter hopelessness. And while I’d be lying if I said I’ve returned to a “relatively stable level of happiness,” some mental paradigm shift has occurred that’s enabled me to go through my day as if it weren’t absurd. I could chalk up this up to the logical result of emergency self-parenting, YouTube yoga, and several just-a-hair-too-long Zoom meet-ups, but the truth is I’d probably get to this place eventually anyway. Not only because I’m extremely privileged to have my home and my health (I am), but also because I’m human.

The question now is whether this sense of relative peace—which feels as precarious as a numbing agent—can be sustained. I know the answer, but part of enduring is pretending I don’t.

I got a desk

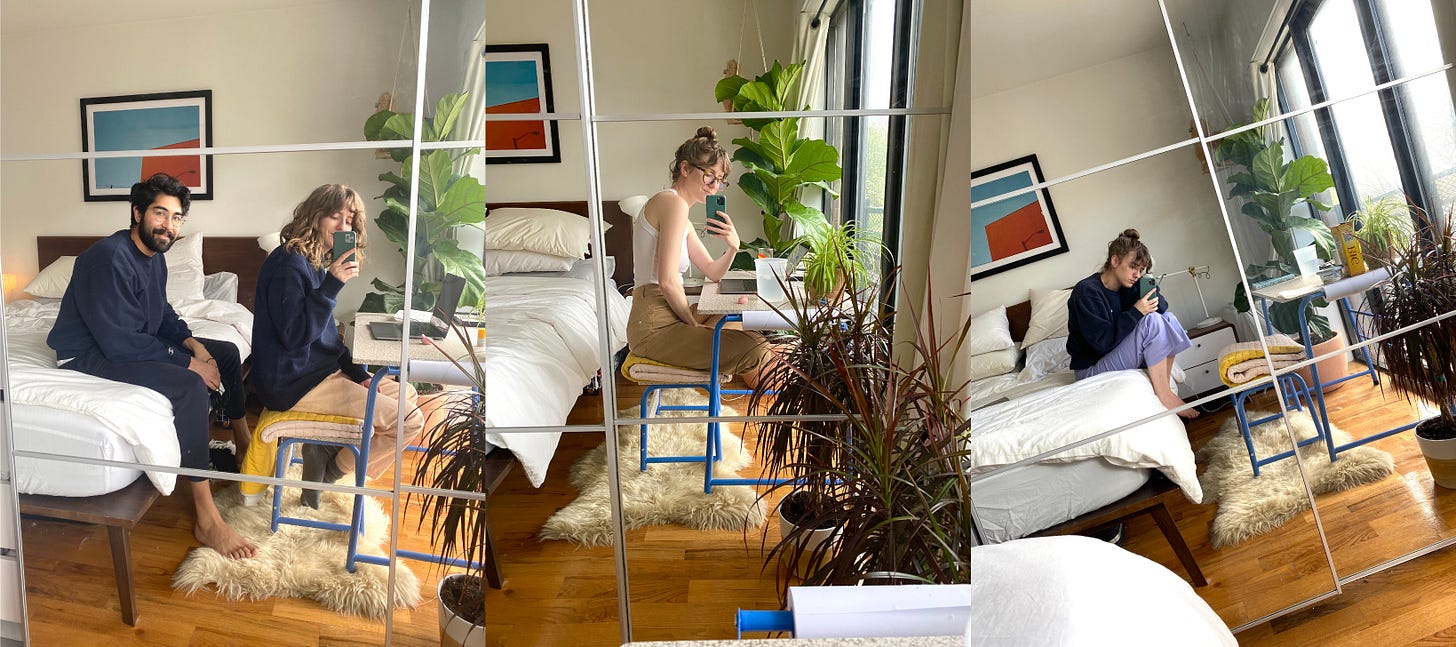

I was on the phone with my therapist last week, discussing my need to establish arbitrary boundaries at home while natural ones (like, say, not being home) aren’t possible. I was sitting on my bed looking out my bedroom window as I said it, and then I thought, a little desk could maybe fit right there. The next day I ordered a kid’s one and it turned out to be the best $100 investment I’ve ever made.

I love it so much. Our bedroom is mostly bed, so I haven’t been able to spend much time in there without feeling bed-ridden. But now I can be in a separate room from Avi for extended periods of time, and I love him so much, but it’s changed everything.

What they don’t tell you about in classic literature: A room of one’s own, with the option to lean back on your mattress.

Sometimes he visits to give me a back scratch. But mostly it’s just me.

And that’s all I have to say on this matter at this time.

Sliding scales

I’ve been thinking a lot about what I want this newsletter to be, and what I want my writing career to look like, two things that feel just meaningless enough (in the scheme of things) to keep my brain distracted without melting it into a porridge. Specifically, I’ve been wondering: What does it mean to launch the next phase of my career in this emotional climate?

If you change the specifics, I’m sure many people are wondering the same. Someone wrote to me that she’d moved to Chicago to start a new life and went straight into quarantine. Another that her boyfriend had broken up with her a few days in and she’d just moved back to her parents’ house. Another that, right before all this happened, she’d turned down a full-time job offer with benefits to pursue a freelance career…in event production. There’s a divine comedy to all of these ill-timed transitions, if we feel safe enough to laugh. They seem intent on reminding us there’s no such thing as a fool-proof plan when life makes fools of all of us.

All the little decisions we made before we knew better, now haunting us, may feel benign in comparison to the societal entropy occurring on a global scale. But these are also the hairpin turns that make up a life. It doesn’t really make sense to discount them on a personal level (unless it helps). I think it’s up to us to do the work of holding them in our consciousness at the same time as everything else, our attention stores functioning like a sliding scale: to each anxiety according to its needs. Or something like that.

We’re still allowed to need things, even in a pandemic.

When I indulge in my own hairpin turn, I’m left with a question: Has my path changed for now, or forever? Before all this happened I had an idea about what kind of writing I wanted to do after I left Man Repeller, but the kind I’ve put out so far is nearly the opposite. I’ve gone super soft, there’s no other way to say it. Everything so sentimental! Metaphors, self-help, you will be okays. Mental health, looking inward, the importance of being earnest. I’ve always been resistant to my own mushiness, so I never expected that “taking the reigns of my career” (...lol) would mean leaning way the fuck into it.

But then again, maybe everyone’s gone soft. Or maybe irony just hits different in a crisis. Or maybe this is who I am, which is of course the answer I dread. Although it’s also kind of funny (in that you should laugh at me).

Going soft

In last week’s newsletter I shared a piece by Leslie Jamison about quarantine, and in reply a reader named Grace recommended another Jamison piece called “In Defense of Saccharine.” It’s an essay from her book The Empathy Exams, and in it she explores the literary world’s resistance to sentimentality. It’s not available online, but Grace sent me a pdf and I read it like my career depended on it.

I’ve never fully understood my own opposition to sentimentality, or why I prefer internet irony to earnest-posting, or am always a little embarrassed by my most personal writing. But I knew it had something to do with my ego, and when I read this part of Jamison’s piece, I felt skewered:

“Perhaps if we say it straight, we suspect, if we express our sentiments too excessively or too directly, we’ll find we’re nothing but banal. There are several fears inscribed in this suspicion: not simply about melodrama or simplicity but about commonality, the fear that our feelings will resemble everyone else’s. This is why we want to dismiss sentimentality, to assert instead that our emotional responses are more sophisticated than other people’s, that our aesthetic sensibilities testify, iceberg style, to an entire landscape of interior depth.”

Damn. I’m always in awe of how many of the world’s ills boil down to insecurity. Wars, dictators, racism, wealth-hoarding, corruption, xenophobia, misogyny, bullying. And somewhere down the list, at a scale nearly invisible to the human eye: My fear of being sentimental.

I’m not afraid my emotions will resemble everyone else’s—I tend to write to confirm they do—but it’s true that I’m professionally insecure, both functionally and emotionally. I can get caught up in wanting to be a certain kind of writer. One who’s respected by a specific subset of New York literati (gross), with a certain kind of Twitter following (grosser), and a blacked-out Bingo-card of bylines at the “right places.” It’s so easy to shape your career goals around arbitrary signposts like this, especially in New York, where people are so often reduced to who they know. But I think at the heart of these superficial desires is a sincere one: to be a good writer with worthwhile ideas. And while I worry that my more sentimental writing may shoehorn me into a certain corner of the media world, it’s probably more honest to say I worry it’s banal. Comforting in the immediate, like sugar, but not ultimately substantive and enduring.

Is this relatable? Maybe you can swap out the details for any career or kind of life we pursue in earnest, subtly charged by egoism and speckled with doubt. What I mean to say is: It’s interesting that my attempt to step away from myself has inadvertently led me right back to where I started. Is this due to extenuating circumstances or because of me? I wonder if others going through ill-timed transitions are experiencing any of the same ironic realizations. Maybe irony really does hit different in a crisis.

I’m embarrassed to be talking about this. These questions of identity and career don’t feel remotely important right now, but I can’t exile them from my brain. I haven’t gotten to that level on my Headspace app yet, which I’ve used once since last February. Instead they must commingle with my fear of mass suffering, societal collapse, and everything I love going away. Apply the sliding scale here.

One thing I do know: I don’t always want my newsletter to look like this—which is to say 1,500+ emotional words—but so far it’s felt appropriate, given everything. Or maybe given me. Either way, if it’s beginning to weigh on you, trust that other versions are coming. As a taste of the variation to come, this one is arriving on a Tuesday. See? Breaking format already.

15 Things I Consumed This Week (and Recommend)

“Tiger King Is a Wild Ride. And Largely Misleading” by Peter Frick-Wright for Outside Magazine. I’m glad I read this criticism, which I found astute, although fair warning: It might sour your enjoyment of the show.

“Garden Song” by Phoebe Bridgers, a song to listen to several times.

The book Less by Andrew Sean Greer, which, per my Instagram story review, I didn’t love the whole way through, but loved in the end.

This Medium article that explains what everyone got wrong about the toilet paper shortage!!!, which I found via Anne Helen Peterson’s newsletter and for some reason read eagerly. Full disclosure, nobody I texted this to agreed to read it, but I believe that was their loss.

I’ll admit I didn’t finish this profile of Dr. Fauci in The New Yorker, but I want to.

Hot 97, New York’s preeminent hip hop radio station. I’ve been getting back into the radio since the aux cord in my car no longer works and I love it.

“Nonvoters Are Not Privileged. They Are Disproportionately Lower-Income, Nonwhite, and Dissatisfied With the Two Parties,” by Glenn Greenwald for The Intercept, which cleared up a lot of misconceptions about nonvoters.

Water, from a quart container, the only vessel from which I now prefer to hydrate.

An old SNL skit: “Liza Minelli tries to turn off a lamp” (thank you Avi)

“The Pandemic Is a Portal” by Arundhati Roy for the Financial Times. A couple weeks late to this one but glad I finally read it.

Smitten Kitchen’s recipe for crispy tortellini with peas and prosciutto. Topically related: Rice-a-Roni still slaps.

Untitled Goose Game, now the only video game I love and will ever love, played on a Switch Lite purchased for me by my brother from a Target in Jersey despite my protests.

Newly thankful for my little trouble-making goose gang.

Bernie Sanders’s end-of-campaign speech (full transcript here), which I watched tearfully. I’m so grateful for his life’s work and the momentum he’s built, I just hope we can keep it up.

This essay of Harling Ross’s for Man Repeller, which is purportedly about rosacea but is actually not at all.

The top Google result for: “is smiling a learned behavior?”, searched at 1:07 a.m. (it’s not).

That’s all for this week. Thank you for reading from the bottom of my corn husk.

Haley

I just wanted to say that I am a big fan of your writing. Could relate to many of the things you said as someone who writes herself - the fear of appearing overly emotional, constantly questioning the kind of writer you want to be, etc. - and found a lot of this comforting. "The hairpin turns that make up a life." I loved that. Keep writing! I'll keep reading. :)

Hi, this is really what I wanted to read at this exact moment, your work always finds ways to help me reckon with myself, gently. You express this worry about the softness you're expressing but it's this exact softness that we need if you've ever read Mark Fisher, a scholar who wrote extensively on capitalism, then you will know that capitalism takes so much from us, more than a lot of are willing to admit. I think if we are to be different after this pandemic, then perhaps all we can really do is lean into ourselves. If we open the door to be more sentimental, there is something so intrinsically human about this that goes against what success narratives tell us we shouldn't be doing, so this is all to say: thank you.

Whatever turns your work takes in this time, know that your words are and have been a place of comfort and home for people like me, who feel so incredibly lost in this time.