Maybe Baby is a free Sunday newsletter. If you love it, consider supporting it financially. For $5/mo, you’ll gain access to my monthly advice column, Dear Baby, as well as my Tuesday weekly podcast. Thank you! (You’ll never see an ad either way.)

Good morning,

Gentle content warning for the essay below, which mentions sexual grooming and abuse, although nothing graphic. And second warning for the tonal left turn when you get to my recommendations for the week, which are notably cheerful (I’ve randomly been in a good mood—we love the hedonic treadmill!). I’m also excited to have my former editor Mallory Rice (who you met on my podcast about Emily Ratajkowksi) and Bustle’s Sex & Relationships Editor Iman Hariri-Kia on my podcast this week to discuss the topic of this week’s essay. I learned a lot from our conversation.

Sex in Hindsight

I’m 12 and a man is swimming quietly towards me in a motel pool. He’s huge and completely submerged, like a shark. He is my soccer coach. He grabs my stomach and I scream. Everyone laughs, including me.

I don’t think of him often, but the feeling he gave me lingers. The way he breathed, the way he stared—each detail is a nut and bolt in the complicated mechanics of my mind, among millions. It’s been a while since I felt inspired to sift through them, but three things I consumed in the last month changed that: A Teacher, a serial drama on Hulu about a teacher seducing a student; “Britney Spears Was Never in Control,” an essay by Tavi Gevinson for The Cut; and Allen v. Farrow, the four-part documentary on HBO about Woody Allen’s abuse allegations. Their through-line, obviously, is sexual assault, a topic that’s been conveyed and debated nonstop over recent years. But their approaches felt different, even refreshing. They knocked something loose.

Specifically, I’ve been considering if and when I’ve been assaulted. Maybe that sounds backwards. You’re supposed to know if you’ve been assaulted; some would argue that’s required. But I do know that I flinch every time a man crosses a woman’s physical boundary in a film or TV scene. Even just a warm hand on a neck, or back, over the clothes, unwanted, will have me turning away, skin crawling, as if I’m watching Texas Chainsaw Massacre. This trigger is so strong and yet amorphous. I don’t think I know its source, but don’t I?

We secretly called the soccer coach the molester—a nickname I later deemed callous and dramatic until I heard, years after I moved away, that he was surreptitiously fired from my middle school for being inappropriate with a child. There was the boyfriend who wanted to have sex when he got home drunk, so I let him do it while a tear rolled silently down my cheek. There was the guy who forced a kiss on me in a dark hallway. The trusted mentor who got too touchy. The man, 12 years my senior, who insisted I was so mature for my age. The guy who asked me to blow him while his friend was in the next room, and got angry when I said no. The ones who didn’t mind or notice if my enthusiasm was feigned, or complained when I couldn’t muster it. All the times I could muster it, imprinting upon me a force of habit so strong I have to actively counter it now.

That I recoil during certain movie scenes might seem like evidence of a repressed memory—some acute trauma you could convict in a court of law. But it’s more likely the result of all my early sexual experiences compacted into something ambient and invisible. It blows through me like a cold chill, and I mistake it for the weather.

What’s compelled me to revisit those moments, these feelings, isn’t some twisted attempt at exposure therapy. It’s more like curiosity. In A Teacher, a show about a high school English teacher seducing her student, the student proclaims his love for her, says he wants to run away with her and that what they have is real. Only years later does he recognize he was abused, and get angry when she says, “I should never have let you kiss me.” The teacher is shocked at his grown-up conviction, so different from the thoughtful openness he conveyed as her “mature” teenage lover. Time lends him a new perspective. Could mine, too?

In Gevinson’s essay for The Cut, she revisits experiences she had when she was 18, including a relationship with someone much older than her. “I now view some of my ‘empowering’ experiences as violating, exploitative, and manipulative,” she writes. “This slow-motion aftershock has been its own traumatic event. I try to reach across time to give my younger self the language for what really went on.”

When I think about the relationship I had with an older man, the one who insisted I was so mature, just like my parents did, I don’t remember feeling meek and manipulated during the course of our six months together. I remember feeling unwaveringly confident in the legitimacy of our relationship. Insistent, even. Just before I ended things for good, I spent my 21st birthday with him on a trip to Chicago, away from my friends, away from the bars I’d been waiting to go to since I arrived at college three years prior. The first night we got there, we went to meet some of his friends at a bar. When I couldn’t get in because I was still underage, I insisted he stay, then spent an hour in a nearby hotel lobby playing Fruit Ninja on my first iPhone. He had two kids back home probably doing something similar. Only now do I realize how sad that trip was. I wonder how all of it made him feel. I wonder what cultural scripts made him feel comfortable coming on to me in the first place. I broke up with him when we landed back in LA.

“If you can still be considered ‘mature for your age,’” writes Gevinson, “you are not an older person’s equal.”

In Allen v. Farrow, a four-part docuseries on HBO about Woody Allen’s history of alleged abuse, the creators examine Allen’s movies for clues as to how he thinks. His fascination with what are generously called “May-December romances” is clear: from Whatever Works (41-year age gap), to You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (39-year age gap), to Hollywood Ending (34-year age gap), to Everyone Says I Love You (30-year age gap), to, perhaps most cringingly, Manhattan, starring a female protagonist aged 17 who falls in love with a 42-year-old man played by Allen himself. (You can see a full list of age gaps in his movies here.) But more unsettling than the casting is the way Allen writes these romances, often with the older man incredulous at the attraction of the younger woman, insisting he’s too old, thereby inviting her to insist he’s not—a trick that lends the illusion of agency to the younger woman, relieving the older man of feeling predatory. The manipulation and grooming described in Allen v. Farrow is mirrored in his films almost exactly, not to mention his scripts and interviews, which are littered with references to abuse. “I mean, if I was caught in a love nest with 15 12-year-old girls tomorrow, people would think, yeah, I always knew that about him,” he said casually in 1976. This is a man who thinks himself so invincible he married his long-time girlfriend’s daughter, who was, at the beginning of their entanglement, 17 to his 52.

Gevinson describes the way her older boyfriend, whom she believed herself madly in love with, would position himself as her inferior, writing, “When my abuser said he thought that it was I who ‘had all the power’ while he was a hapless, insecure, wealthy, much-older-than-me man who didn’t know what he was doing, I at first believed him.” I don’t recall my older boyfriend playing that particular card, nor do I think of him as my abuser, but I’m intimately familiar with the contradiction of being told you’re powerful despite feeling nothing like that. In fact, I don’t know a single woman who hasn’t at some point internalized the idea that her refusal is so powerful she must prepare for, circumvent, or avoid its consequences. Maybe everyone has experienced this dissonance in some form: a sense of power disoriented by someone else’s terms.

This isn’t just about men and women, young and old, or even about abuse specifically. It’s about social dynamics, and how they form us. In movie scenes that trigger me, it is almost always between two people who are intimately familiar with each other, where a level of trust is implied. And it is not the touch itself that makes my skin crawl, but the calm reception of it. The belief, transmitted via unmoving expression, that one must remain stoic, or even soft, in the face of unwanted advances, to preserve feelings, peace, reputation, safety. A compensation that becomes so ingrained, so instinctual, that it starts to register as a quirk of personality, or biology, or even kindness. We’ve talked about these things enough—gray areas, manufactured consent—but whenever I recognize them in myself, I’m surprised anew. I see things I didn’t see before; a tectonic plate of my past shifts. “I thought I was too exceptional to be taken advantage of,” Gevinson writes.

When accusations of “sexual misconduct” go public, the discourse that follows is almost always one of debate. Not just about whether the accuser is telling the “objective” truth, but whether what happened “counts” as assault, whether the accused did it intentionally, or what level of punishment is deserved. I understand why these distinctions are important in court, but I wonder how much they serve us in the social sphere, at least to the extent that they replace broader systemic critiques. Sometimes I think we’re so collectively committed to the penal system that we can’t help but imitate it ourselves: deciding who is guilty and who is innocent, bifurcating people into good and bad, making and amending the rules. But as we saw with some of the fallout of #MeToo, trying to identify every shade of gray has diminishing returns. It spotlights individual instances, leaving out those who don’t speak out, or can’t, or would never think to. Hedging against every wrong moment or bad actor, then, is only the first step, like batting at individual flies in the kitchen before dealing with the rotten food that drew them there.

The boy who got angry when I said no, his friend in the next room? I don’t think he was cruel; he just didn’t understand how it felt when he asked me to do things I didn’t want to do, or what it meant to express disappointment when I hesitated. I don’t know how he felt either. We were 19. It would have helped had we both received a better education about how to say no (me) and how to wait for an enthusiastic yes (him), but what about the far more unwieldy problem of why those instructions need to be given in the first place? And why they feel gendered? And why they’re so hard to follow? I’m not suggesting that nothing is anyone’s fault, or that more nuanced sexual education isn’t critical, but some experiences defy definition. Sometimes we say yes when we mean no. Sometimes what we “want” is shaped by other factors than desire. Sometimes it all shifts with time and hindsight, presenting as a shiver or a bad feeling or nothing at all.

After the initial swell of the #MeToo movement, I grew increasingly numb to the conversation. Reading about trauma with my brain soft and open like a wound became untenable, even as I was grateful the silence was breaking. I also grew tired of feeling defined by my gender, by victimhood. I didn’t—still don’t—want to feel “empowered”; its mere pursuit makes me feel stupid. I also understand myself to be one of the lucky ones. This reticence has made me less comfortable exploring my sexual past, afraid of what it might say about me, or men, or society. But after I finished A Teacher and read Tavi’s essay, and as I watch Allen v. Farrow, I feel called back in a new way. Rather than merely depict the lurid details, or exist for the sake of proving their existence, these works examine the emotional currents surrounding them: a student’s infatuation, Tavi’s teenaged confidence, Allen’s way of seeing the world—each of them skewed by the passage of time.

It’s through this lens that sex, power, and agency become impossibly entangled. When my family didn’t accept my relationship with my older boyfriend, I felt hurt, disrespected, and alone. Were they right to reject me by rejecting him? I broke up with him as a result. A small part of me still resents their coldness, even if I understand it. In Allen v. Farrow, Mia Farrow grapples with her decision to allow Allen around her children after she discovered he was having an affair with her daughter, Soon-Yi—an arrangement that gave him more time around their other daughter, Dylan. She appears strained on camera, unable to square her failure to see what became obvious to her later. ”[I]n that moment, I realized just how acquiescent I had become.” That’s not Farrow, but Lindsey Boylan, in her recent Medium post about New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s inappropriate behavior. History doesn’t write itself.

There’s something unsettling about recalibrating the narrative, personal or otherwise. To see something differently in hindsight disrupts our self-mythology. It changes everything that happened before, during, and after. Positions of power switch, mysteries become obvious, mistakes become prophecies. We change as a result. To me, this type of reflection registers on a different emotional scale than defining our past in terms of where and how we were wronged, or wronged others. It feels more exploratory than diagnostic; less pointed than systemic. It doesn’t have to be anyone’s fault, or rather: assigning blame isn’t necessarily the goal.

I understand why the conversation around assault, harassment, and the gray areas in-between became focused on accountability, but I wonder what else lies beyond that heat-seeking missile. I wouldn’t claim to know, I’m only curious, meaning less numb, which feels like a positive development.

1. My most emphatic rec of the week: In & Of Itself on Hulu. I saw this live in New York with my family and it was hands down the coolest show I’ve ever been to. I was nervous to watch the taped version but it held up surprisingly well and managed to make me sob (again). My suggestion is to not look up anything about it—just watch it. It’s weird and surprising and will make you feel good.

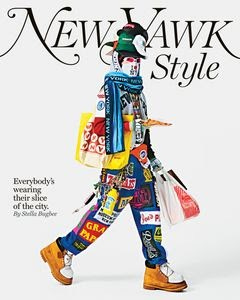

2. “Thank You, Dr. Zizmore,” a style piece by Stella Bugbee for NYMag about New Yorkers’ penchant for local memorabilia (wearing my Economy Candy t-shirt as we speak). A really fun read that transported me to a version of New York not gripped by crisis. Also my friend Bobby Doherty shot the cover and I can’t stop looking at it.

3. THIS TRICK THAT ACTUALLY WORKS: Put a wet paper towel on the cutting board when you’re chopping onions and your eyes won’t water!!! Sometimes TikTok delivers.

4. This chart, care of a reader, about which day is considered “the first” of the week, by country. The idea of Sunday being last? Philosophically it does make sense, but I do think it’s fucked up.

5. This malted “forever” brownie recipe by Claire Saffitz. Easily the best brownies I’ve ever eaten and I don’t even care about brownies! They tasted like a double chocolate cookie from Levain. (Also used these new mise-en-place/prep bowls I got from William Sonoma while baking and reached a higher plane.)

6. The genuinely touching suggestion under a Yoga With Adriene video that you refresh the view count after you finish a session to see how many people were doing it with you at the same time. When I did it the number jumped like 10,000. 😭

7. “5 Pandemic Mistakes We Keep Repeating,” by Zeynep Tufekci for The Atlantic about how the public message around covid backfired, and also about what that means for the future (it’s optimistic!). If you only read one piece this week let it be this. (This other, shorter, Atlantic covid piece made me hopeful too.)

8. This little humidifier by Canopy. This was actually a gift from Open Spaces because they just collaborated with Canopy on three diffusion scents (for morning, afternoon, and night), but we’ve been running it like our lives depend on it. Happy to report Bug’s nose is now in peak soft-and-pink form. (I once linked to our Open Spaces shoe rack on this very newsletter, hence the gift. I really do love the shoe rack…)

9. A new scientific finding: kombucha tastes better through a straw.

10. “The Story of ‘Thong Song’ by Sisqó,” an oral history on Vice’s YouTube channel that is surprisingly incredible, coined “the feel-good movie of the year” by one Avi Bonnerjee. I have to agree.

11. “Britney Spears Was Never in Control,” by Tavi Gevinson for The Cut, obviously.

12. The stunning realization that you can communicate with your cat via slow-blink. I swear to god my relationship with Bug has completely changed! He sits on my lap now!

13. “Acting Black and White on Screen,” an immersive essay by Hilton Als for The New Yorker that examines the evergreen question of what makes art resonant (answered in his specific and surprising way).

14. This crispy smashed potatoes recipe by Alison Roman, for the fourth time in lockdown. They’re so good I want them right now.

15. Dune. I finally finished it! Then watched the famously disowned movie by David Lynch. Agreed with Lynch that it was bad but also loved it on principle. Ready for Timmy Chalamet’s debut as Paul this year.

That’s all for this week. Thank you for reading! And thank you to those who have been using my feedback form. I made it assuming the feedback would be primarily critical, but it’s been thoroughly uplifting instead. I appreciate the time you take to read this newsletter, it makes me want to keep going.

I’ll see you next week!

Haley

This month a portion of subscriber proceeds will be redistributed to GlobalGiving Coronavirus Relief Fund, a non-profit focused on equitable vaccine distribution and getting resources to those made especially vulnerable by the pandemic.

Give me feedback • Subscribe • Request a free subscription • Ask Dear Baby a question